Summary: The question of what to call the army tasked with fighting the British highlights some of the complicated dynamics in play during the Revolutionary War.

Armed Conflict Begins in America

Before the Revolution broke out, America was comprised of twelve distinct colonies (Delaware had not yet separated from Pennsylvania), each with their own governor, legislature, and judiciary; and each colony had their own issues, grievances, and goals. In October, 1774 delegates to the first Continental Congress realized that they shared common gripes and goals. They agreed to embargo British goods until Parliament repealed oppressive laws, they sent a letter to King George III hoping the King would act to resolve the situation, and went home. When Massachusetts’ militia stood up to British “Regulars” six months later at Lexington and Concord there was no “United States,” no American army, and Continental Congress wasn’t even in session.

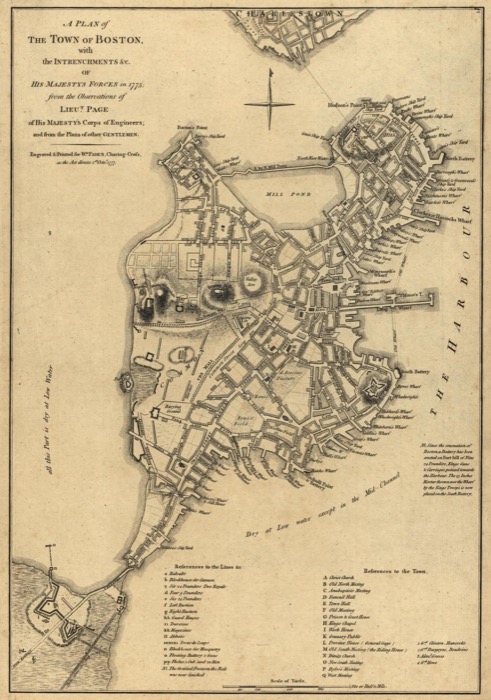

The “shot heard round the world” triggered a previously agreed “attack upon one is an attack upon all” response, and armed New Englanders rushed to Massachusetts. They quickly controlled all the land approaches to Boston, trapping the 14,000-man British army in Boston. Sort of like the dog who caught the car, they had little idea, or agreement, on what to do next.

Since the fight was in the sovereign colony of Massachusetts, their Committee of Safety took charge. They named General Artemas Ward, a French and Indian War veteran, as commander of what they called the “Army of Observation” surrounding Boston. But it quickly became apparent that New England wasn’t prepared to maintain an army in the field, nor to recruit, train and equip the additional men needed to defeat the British army – the best in the world at the time. Plus, they were losing control: when Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys captured Fort Ticonderoga, the war escalated into New York, a situation that the New England colonies were not prepared for. Once Congress reconvened in May, 1775, New England asked for help from the other American colonies.

Congress was reluctant to establish an army. After all, the British maintaining a standing army in America was one of the primary gripes that all of the colonies shared. Nor did Congress have the money required to maintain or pay a standing army. Yet, it was clear an army was needed, and that it needed central control.

A Centralized Army

Despite its reluctance, Continental Congress began steps to create an army on June 14, 1775, when they voted to form and provide pay for ten companies of riflemen formed in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania to join the fight outside Boston. Though established in theory, Congress’ army did not exist in substance until they appointed George Washington to command it, and he did not arrive outside Boston until July 2nd to take command of the “Army of Observation” from Artemas Ward. The actual name of that army… well… Congress, and everyone else, struggled with that.

The confusion of what to call that army stems from the problem that Continental Congress did not actually “name” it. A primary reason for not naming it was the pretense that America was not at war with Britain. Rather, up to this point American colonies were asserting their rights as British citizens, officially seeking reconciliation with the Crown: if you have an officially named army, you’re no longer just a bunch of irate farmers sticking up for yourselves.

Since Congress didn’t officially name it, they used various terms to describe it in the Journals of the Continental Congress and official correspondence. They said it was “continental” as a lower-case adjective to describe or designate the forces distinctly from provincially raised militia or minutemen. They frequently called it “the Army before Boston,” again, to distinguish it from other forces.

On June 20th, 1775, they appointed George Washington as “General and Commander in Chief of the Army of the united Colonies” including “forces to be raised for the defense of America.” Elsewhere they called it the “united Army.” When discussing pay for militia attached to the “main army,” they resolved pay be the same as the “officers and privates of the American Army.”

In an age when writers capitalized anything they thought might be critical, the use of capitalization reveals that throughout these initial writings and discussions Congress struggled with its failure to name the army. “continental,” always with a small “c,” is consistently used to describe the commitment to the general defense of America, meaning it was not limited by the boundaries of any province or colony; and also meaning that pay and specific supplies would be provided by Congress (as opposed to being paid by the colony which raised the unit).

Congress was still struggling with what to call “it” when they began writing the “Articles of War.” These “Articles” are what we would modernly call regulations for the army; describing the behavior expected of those who serve. In Article I (Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume 2, pg 112, 30 June 1775), Congress starts right off by addressing who the rules are for:

“ …every officer who shall be retained, and every soldier who shall serve in the Continental Army…”

We might think they’d settled on a name, but the very next day they used different language: “the Army of the United Colonies.” Throughout 1775 the naming convention remained in disarray, confusing, and left room for doubt as to exactly what group of troops was being referenced in any particular message. <Sigh>

The enlistment period for Washington’s entire army, except for the ten companies of riflemen, expired December 31, 1775. The entire army had to be rebuilt, requiring new enlistments. For a couple months Boston was surrounded only by local militia who’d agreed to stay on. Washington wrote about the rebuild as a “new army, which, in every point of View is entirely Continental” and told Congress that the new army would be “Continentally aligned.”

Washington moved the officers to new commands so they were not commanding their friends from home, and rather than calling regiments by their commander’s name, the new army would be designated by their state and a number; and would be designated as “continental Regiments.”

Although Washington made the mental shift to a “continental” establishment. Congress did not. Following its declaration of independence in July 1776, Congress no longer needed to shield the existence of the colonial army from British criticism; and realized it was no longer “colonial” but a “national” army.

A Continental Army

Congress ordered a new batch of officer commissions to be printed which stated officers were serving in the “Army of the United States.” By mid-1777, officers were being commissioned into the “Army of the United States,” while soldiers were still enlisting into “continental Service.” Nouns versus adjectives. Who knew 5th grade English could matter so much?

This leads us back to our question. Since Congress never officially named the “army serving in Defense of American Liberties,” why do we refer to it as the “Continental Army?”

Because of Tench Tilghman.

Tilghman was Washington’s longest serving Aide de Camp. At the outbreak of war Tilghman was given a mission to negotiate a treaty with the Mohawk Tribe in New York. After successfully brokering the deal, and becoming the Chief’s adopted son, Tilghman joined Washington in August 1776 and served throughout the war. Tilghman refused rank and pay until Washington went behind his back to Congress, who corrected the situation in May 1781.

Tilghman became responsible for submitting weekly and monthly troop strength reports to Congress. His reports for October 1777 included not only the troops in the Main Army under Washington’s direct command, but also included those in the Northern, and eventually the Southern, armies. He maintained the same format until the army was dissolved in November 1783, titled:

“A Weekly Return of the Continental Army of the United States of America Under the Command of His Excellency General Washington.”

In the end, due to the lack of official designation, the Continental Army was named by a diligent staffer duly submitting his reports. Tilghman’s moniker stuck. Modernly, when we call it the “Continental Army” we are really just abbreviating the title Tilghman used for his reports; reports which now form our primary source about the strength of Washington’s army (Tilghman’s reports are collected in a large book published during the bicentennial called “The Sinews of Independence,” compiled and edited by Charles Lesser).

Conclusion

Although we call it the Continental Army, perhaps Washington should be given the final say. On the evening of November 2, 1783, with the men who won America’s freedom to be officially discharged and the army dissolved the next morning, Washington sent compliments to his troops by ordering the Philadelphia newspapers to print and disseminate his “Farewell Orders issued to the Armies of the United States of America.”

TOP PHOTO: George Washington alongside his generals at Yorktown, Virginia. Peale’s imagined gathering includes the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) on Washington’s left, Comte de Rochambeau (1725-1807), commander of the allied French troops, third from the right, and Colonel Tench Tilghman (1744-1786) who is seen in profile, holding the articles of capitulation that he later delivered to Congress. (credit: By Charles Wilson Peala (1784), Maryland Center for History and Culture)