Summary: Coming up with a national currency that would retain its value and be suitable to pay soldiers in the Continental army was a major challenge during the Revolutionary War.

Military Pay During the Revolution

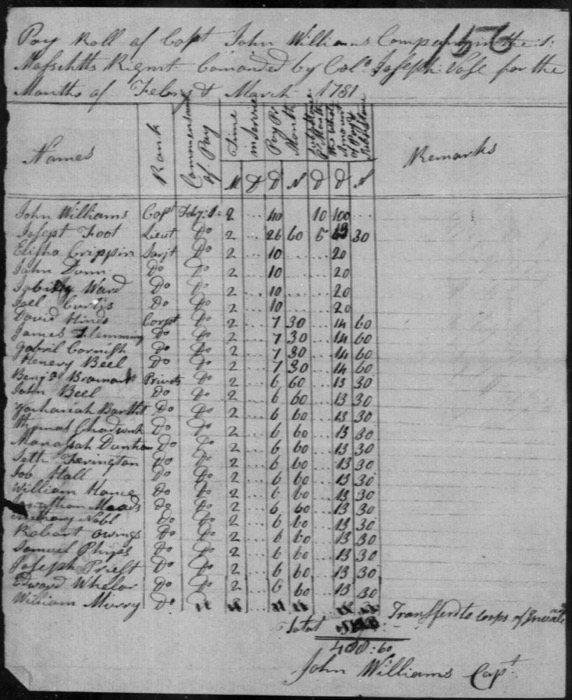

Continental Soldiers were paid six and two-thirds dollars per month. Truly a paltry sum for putting their lives at risk of disease, artillery, musket ball, bayonet and accident; in order of the leading causes of soldiers’ death and disability during the revolution.

In previous articles we’ve learned that the first soldiers to fight in the revolution were state or local militia; the “Continental Army” did not come into being until the Continental Congress adopted the concept in June of 1775 and appointed George Washington as Commander-In-Chief. When Washington arrived in Massachusetts, in July 1775, to take command of the various militia entities besieging Boston, those militia soldiers became Continentals who had to be paid by Congress. But how to do it?

Creating the Continental Dollar

At the outbreak of the Revolution none of the European currencies circulating used a decimal, or metric, system. The British pound was our national monetary system – we were not only using British currency, but once the war broke out each of the rebelling American colonies were printing their own currency based on the British pound system.

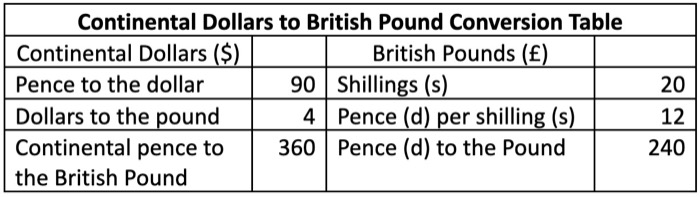

The British pound was made up of 20 shillings, and each shilling of 12 pence. Further, each pence included two halfpence (“ha-pennies”) or four “farthings.” This meant that there were 240 pence to the British pound (960 farthings, ugh). When prices were stated, they were stated as pounds (£), shillings (s), pence (d), farthings (q): £ – s – d – q. A stated price of 1 – 19 – 11 – 3 is read as 1 pound – 19 shillings – 11 pence – 3 farthings; which is one farthing short of two pounds… sort of the 18th Century equivalent of $1.999 (if we had three decimal places).

The 13 American colonial currencies each had different exchange rates with the British pound, such that a paper pound note printed in Connecticut did not equal that of New Hampshire or one of the Carolinas. Unlike most other colonies, Virginia’s currency could be used to pay taxes, and Virginia laws provided that set amounts of tobacco, corn, flax, or hemp could be provided for taxes, too – such that Virginia’s currency was “hardened” by being interchangeable with a set amount of crops; which had a consistent value.

Congress was getting currency and supplies from each of the 13 colonies, as well as from sympathizers and governments outside America. All of this meant that accounting for purchases of supplies for the war effort required dealing in 13 colonial currencies of fluctuating exchange rates; plus British, Spanish, French, Dutch, German and other currencies. At this point your brain should hurt, it was a financial nightmare; Congress needed to simplify.

One of our major gripes with Britain was that the Currency Act(s) meant there wasn’t much hard currency (coin or “specie”) circulating in the American colonies. Of what was circulating, the primary coinage was British, and the primary coins were the shilling and the pence – or “penny”; whether it was a bronze penny minted in Britain, a wooden penny from New Hampshire, a paper penny from Connecticut, or a bronze coin from Virginia.

Congress’ challenge was to devise a currency system that leveraged existing British coins and be readily exchangeable with the pound system. They also wanted it to be compatible with the primary international coin in use at the time. Although “officially” illegal in British colonies, American traders engaged in both legal and illegal trade in the Caribbean were familiar with the Spanish milled dollar: it was the second-most prevalent currency circulating in the colonies.

The Spanish had come up with a rolling press that could “mill” pressed coins of reliable consistency in weight of metal, and, because Spain controlled the silver and gold mines of Central and South America, the milled dollar was the most widely circulated coin of 18th Century world trade. It could even be cut into pieces of eight, or “bits,” to make change. The Spanish dollar was a key to the international trade from which Britain had prohibited Americans from engaging.

Not worth a Continental

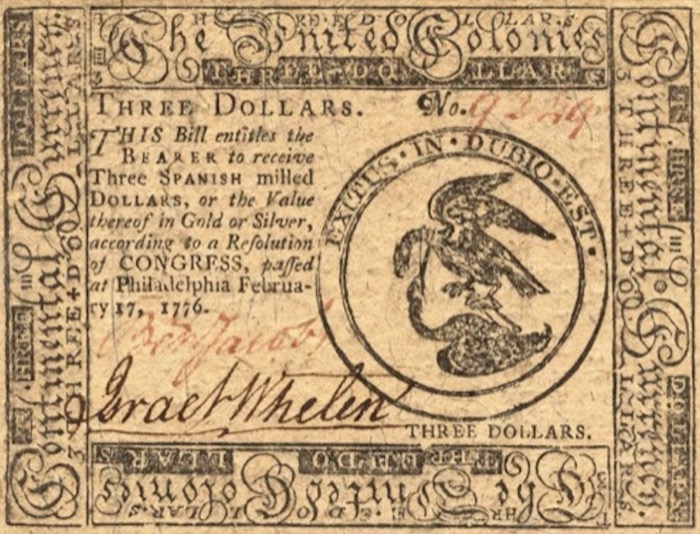

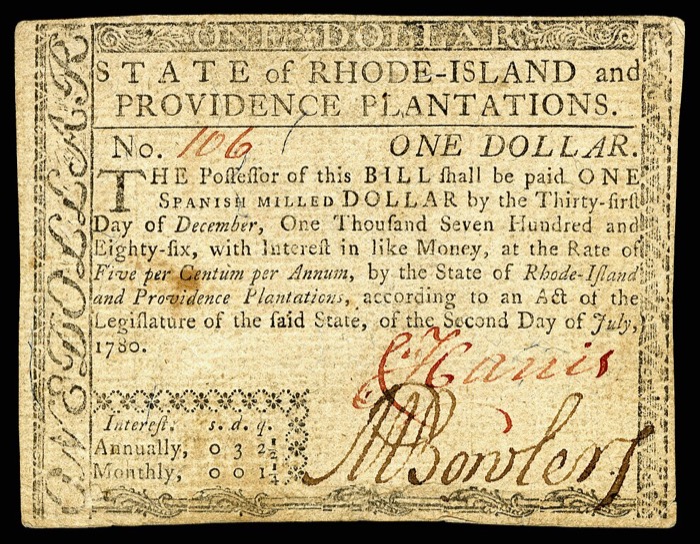

To address this need Congress created the currency that became known as the “Continental Dollar” and authorized its first printing on July 29, 1775. The notes were dated May 10, 1775, the opening date of that Congressional session. In that year Congress printed $6,000,000 in paper currency; bills that were more like what we now know as “savings bonds” rather than a modern bill or coin. That’s because the value of currency in the 18th century was measured by the amount of precious metal in the coin itself. The weight of metal coins was known, there was a fixed exchange rate based on the amount of bronze, copper, silver or gold in a British silver shilling, versus a Spanish milled dollar, versus a French livre, versus the German Groschen, versus the Dutch rijksdaller, ducat or guilder.

In these countries paper currency could be exchanged for coins of the same valuation, ensuring paper currency held the value of precious metal. But Continental Congress did not have any precious metal other than a few coins of other nations…they planned to borrow it. The Continental dollar was a paper promise: Congress promised to obtain precious metal by certain dates at which time they would redeem the paper currency, plus interest, in exchange for the coin or bullion.

The idea was that Congress would borrow bullion or coins (specie) from other countries and then, when the bills matured, Congress would buy back the Continental dollars with the borrowed specie; then burn the redeemed paper currency. Bills issued in 1775 would be paid off starting in 1779. In theory, the interest would make the bills more valuable as they neared their redemption date, combatting inflation. In reality, Congress was unable to get loans as quickly as required, making them unable to provide precious metal for the first redemption.

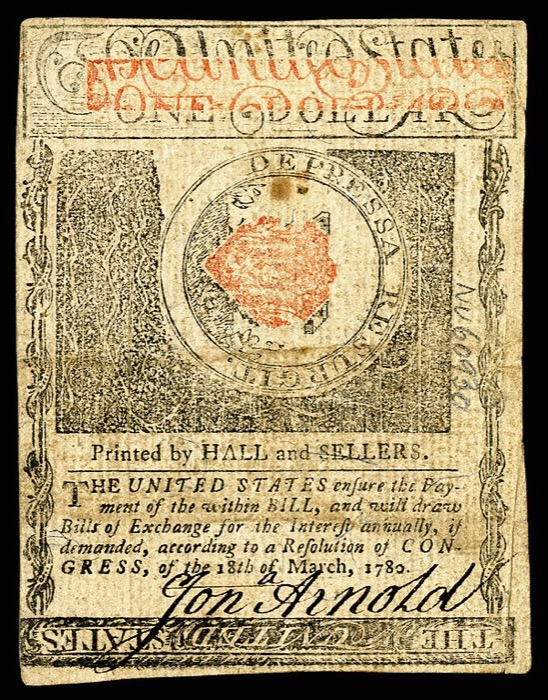

Instead, Congress paid the first redemption with new, freshly printed bills promising payment at an unstated future date. Additionally, Congress had continued to print money as the expenses of the war had grown and did not tie the paper money to a hard commodity. The $6 million printed in 1775 had grown to $199,990,000 printed by the end of 1779.

To make matters worse, Continental Congress President Henry Laurens was captured by the British while enroute to Europe to obtain the hard currency specie loans from France and Holland necessary to redeem the Continental dollars. British agents exploited the situation by introducing vast amounts of counterfeit currency; some estimates suggest Britain counterfeited nearly twice as much Continental currency as Congress actually printed.

After the redemption failure, by 1780 the Continental dollar was trading at 1/40th of its original value. By 1782, following rampant British counterfeiting, 1/100th, and by spring of 1783, the state of Virginia listed the tax value of the Continental Dollar at about 1/1000th of its face value. Hence, at the end of the war an object that had no value was disparaged as “not worth a Continental.”

The 1776 Continental Dollar coin, pewter version, utilizing a combination of several designs drawn by Ben Franklin or Continental currency. Although coins were never authorized by Congress, about 6,000 of these were stamped by Elisha Galludet, probably in New York City in February-March 1776, in lieu of printing paper Continental dollars authorized by Continental Congress. Most were in pewter, though a few examples in tin, brass and silver survive today. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Although flawed in execution, Congress’ intent was brilliant in several aspects. They labelled the new currency as Continental “dollars” and gave it the same exchange rate as the Spanish dollar; four dollars to the pound. This made the Continental dollar theoretically compatible with the silver Spanish milled dollars already in circulation. Next, they built in compatibility with the British pound system by giving the Continental dollar the value of 90 pence (yes, you read that correctly, there were only 90 pennies in America’s first dollar).

At 12 pence to the shilling, and 240 pence to the pound, the key divisor that enabled exchange to British currency (and to French, Dutch and German currency), was six. 100 is not divisible by six, but 90 is. Plus, given there are 90 pence to an American dollar, and four dollars are in a pound, then 4 x 90 = 360, meaning there are 360 Continental pence equaling a British pound comprised of 240 pence. So, 1 ½ American Pence equal 1 British pence. Since the British conveniently made halfpennies and farthings, the British coinage circulating in America could be used in the Continental monetary system. The four to one ratio also made the conversion between continental dollars and the 13 colonial pound-based currencies relatively simple for wartime accounting.

Back to the soldiers

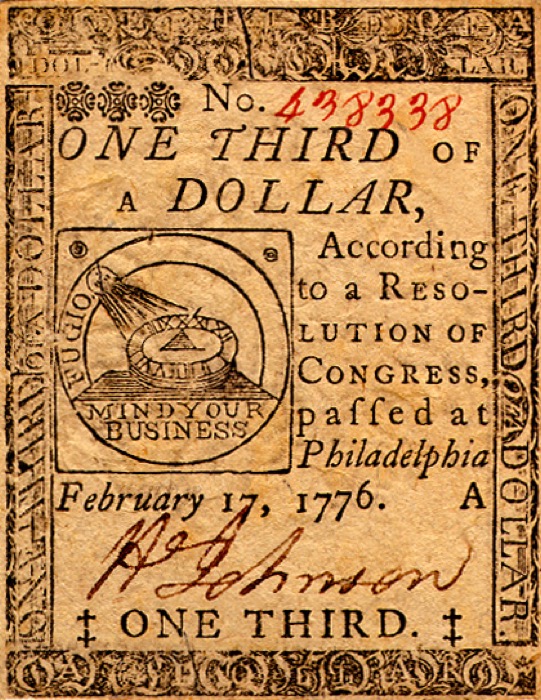

Continental soldiers’ pay was deliberately designed to be slightly more than that of a British soldier. The British army paid soldiers about one shilling a day, actually 30 shillings per month. At 20 shillings to the pound, British soldier pay was about one-and-a-half pounds per month. With the value of the Continental dollar equal to the exchange rate of the Spanish milled dollar, four dollars to the British pound, British pay of one and one-half pounds equaled 6 dollars per month. In setting Continental soldiers pay slightly higher, at 6 and 2/3 dollars per month, Congress set a rate that made service in the Continental army favorable in comparison to the British – or Hessian – armies… And that 2/3 of a dollar? Now you know it was worth 60 Continental pence.

Congress’ plan was effective until they failed to redeem Continental dollars for bullion or coin in 1779. They quickly realized the toll depreciation took on the Continental dollar, but were slow to understand just how much British counterfeiting was impacting valuation.

In 1780 Congress ordered the states to begin reclaiming continental dollars and allowing issue of only one new dollar for every 20 reclaimed, but the British were flooding the American economy with fake bills. Depreciation of the Continental dollar made it virtually worthless by war’s end.

In November of 1783 Washington’s Continental Army was discharged. Almost all of them, whether at Charleston SC or Newburgh NY, drew their final pay in Continental dollars, usually including months or even years of back pay. It was all they had to make their way home on foot from West Point to Virginia, or Savannah to Pennsylvania. Speculators met them at the camp gates and offered pennies for their worthless script, and the soldiers sold it in exchange for the coins needed to buy food on the winter slog home. Almost a decade later, embarrassed by the treatment afforded Continental veterans, the United States Congress agreed to buy back the original script at face value, giving freshly minted coin in exchange for Continental dollars. Unfortunately, most of those still holding Continentals were speculators who had taken advantage of the troops at war’s end.

Conclusion

In 1792 Congress passed the Coinage Act, which established a new US Dollar (USD) as the value of a Spanish milled dollar, to contain 371 ¼ grains pure silver or 416 grains of sterling (“standard”) silver. The act denominated the dollar based on a decimal system comprised of 1,000 “mils” (₥), equaling 100 “cents” (¢), ten “dimes” (10 cents each), the “dollar,” and the “eagle” (a unit of ten dollars). Modernly, we no longer refer to a ten-dollar bill as an “Eagle,” and only see “mils” displayed on the gas pump; that mysterious third decimal place which always seems to be a “9.”

The “bit,” which was 1/8 of a dollar (12 ½ cents) taken from the Spanish “Real,” or 1/8 of a Spanish milled dollar (formally called a “Peso”) remained a formal designation until 1854, and remained a unit of measure on the US Stock Exchange until 2001.

As a result of the experience with paper script, America avoided paper money until just before the Civil War, when another generation of American Soldiers referred to the worthless fractional-dollar script as “shin plasters.”

NOTE: The dollar sign ($) is used in this article for simplicity to denote Continental currency, however the dollar sign was not adopted for use by the United States until 1785, when it was adapted for the Spanish symbol for the Peso.

TOP PHOTO: Continental 3-dollar bill printed in Philadelphia in June 1776. Continental bills came in many different denominations that would seem strange to us today, but were efficient in the typical sums of the 18th century. Continental soldiers, when actually paid, received two of these and two “one third dollar” bills for their monthly pay of six and two-thirds dollars per month. (public domain via Museum of the American Revolution).