Summary: Christmas celebrations in colonial America were far different than they are today.

Early Views of Christmas

With big-box stores announcing the impending Christmas season with carols at about the same time Halloween candy appears on their shelves, we have been modernly brainwashed into believing that Christmas has been universally celebrated ever since the Three Kings of Orient presented gifts to a little child Away In A Manger in the Little Town Of Bethlehem. But, in colonial America, where it was celebrated, it was far different than now.

The Bible gives no date for Jesus’ birth. Mary and Joseph travelled to Bethlehem during Caesar Augustus’ census, which lasted more than a year. It wasn’t until three centuries after Christ’s death that the Catholic Church declared December 25th of the old Julian calendar as the date for “Christ’s Mass.” The date was retained by Western Christian churches after the new Gregorian Calendar was established, while Eastern or Orthodox Christian churches celebrate on January 7th, which corresponds to December 25th in the previous Julian Calendar.

The early Church largely ignored Jesus’ birth; the important aspect of our redemption and Church focus was on Christ’s death and resurrection. Many early Christmas traditions were adapted from pagan or Roman rituals that existed around the winter solstice as a way of blending old traditions into the new religion. After the Reformation, many Protestant churches wanted to shed trappings of Catholicism, including Christmas traditions.

Christmas in the New Colonies

By the time of America’s European colonization in the early 17th century, English Protestantism was divided over the celebration of Jesus’ Holy Day, Christ’s Mass. The Anglican church did not hold services specifically for Christmas day, recognizing the Nativity on the nearest Sunday, but did not forbid celebrations. For those who did celebrate the season, festivities were secular rather than religious. Christmas was not a day, but a “season” lasting 13 days: Christmas day through the Twelfth Night of January 6th, avoiding the Eastern Orthodox Catholic Church’s celebration of the Nativity on January 7th. English traditions at this time included gathering to play games in homes or taverns or going caroling, often called “wassailing” as the tunes were performed in hopes of an invitation to share the host’s hot mulled wine or “wassail.”

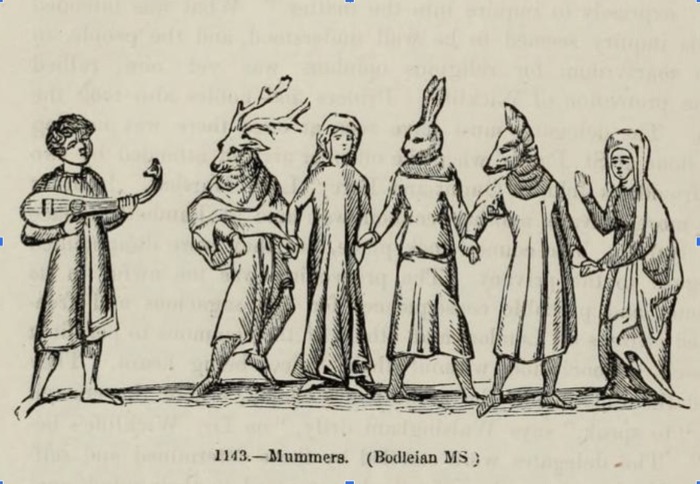

Carols began to be sung as early as 450 A.D, and Christmas caroling developed in the Middle Ages. Some of the oldest songs we still sing, like “Good King Wenceslas,” are Christmas carols. By the mid 1700’s most Anglicans knew the tunes and words of Isaac Watts carols, including his most famous, “Joy To The World,” written in 1719. “Mumming” was also popular. Adults would dress up in costume: as members of the opposite sex, forest creatures or trees, or persons of notoriety; then visit wealthy homes offering songs, a brief play or “pantomime,” and recited prayers asking for blessings upon the host in exchange for a festive glass or a monetary donation.

At the same time the Puritan church disdained vile Christmas celebratory activities as Papist or pagan. Puritans maintained Christmas as a work day and banned all frivolity. Once Puritans rose to power in Britain and deposed King Charles I, Christmas celebrations were officially quashed. At this time in early colonial America, even as Christmas season frivolity continued in Anglican areas, New England Puritans (Congregationalists) suppressed celebrations of any sort. Celebration of Christmas was legally banned in the colony of Massachusetts from 1659 until 1686, and unofficially repressed until the mid-1800’s. Such “festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries” were a “great dishonor of God and offence of others.” The “Penalty for Keeping Christmas Law” also banned celebration or “forbearing of labor, or feasting” of Easter, Whitsunday, or any other notable day (including birthdays) under a penalty of 5 shillings, a substantial sum at the time. Quaker, and later Presbyterian and Baptist churches joined in the Congregationalist ban on Christmas celebration.

In 1749, Peter Kalm, a Swedish visitor to Philadelphia, wrote regarding Christmas day: “The Quakers did not regard this day any more remarkable than other days. Stores were open, and anyone might sell or purchase what he wanted…There was no more baking of bread for the Christmas festival than for other days; and no Christmas porridge on Christmas Eve! One did not seem to know what it meant to wish anyone a merry Christmas.”

Kalm also mentioned that the Presbyterians relented when they realized their parishioners were attending Anglican services on Christmas, and soon began their own Christmas services. 100 years later Ebenezer Scrooge would relate: Humbug!

New Ideas Come to America

The Great Awakening of 1730-1740, broader multi-national immigration and emerging ideas that religious observance ought to be between the individual and God somewhat softened stances on Christmas celebration. Still, other than a few Catholic and German Lutheran congregations, there was scarce religious observation of Christmas day unless it fell on Sunday.

European travelers in America described the difficulty of finding an open church on Christmas day, and complained that even if open, there were no services nor even a minister present, a situation we find hard to imagine today. As a result, those colonial Americans who celebrated did so engaged in secular Christmas festivities as a “season” lasting 13 days. Rather than a religious observance, it has been described as a “community party.”

By the time of the 1770’s and the start of the American Revolution, many Anglican churches held Christmas day services and the Christmas season was generally celebrated in America with socializing in taverns, dining, drinks, games, and dancing at balls. Societal generosity and caroling were popular forms of mirth, and Americans performed the custom of firing guns to welcome Christmas Day (and New Year’s); sometimes several times during the day. Americans decorated inside homes, churches and businesses with evergreen boughs, including fir, holly, boxwood, mountain laurel and magnolia. Mistletoe was hung and its kissing tradition observed.

The “creche” tradition was started in America when Herrnhut Moravians (formerly Bohemia, now the Czech Republic) established Bethlehem Pennsylvania on Christmas Eve of 1741. They copied the Nativity scene tradition from their homeland, which was common to later Moravian settlements across America. While it spread to German Catholic and Lutheran communities in the later 1700’s, it was not adopted in English speaking settlements until the mid-1800’s.

Gift giving was not a customary part of Christmas at this time. The song, “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” first published in English about 1717, is actually a courtship song. Because the deepest part of winter provided a break from the daily grind of farming, the Christmas season was a very popular time for marriages; for example, George and Martha Washington were married on Twelfth Night, Jan 6, 1759.

Although gift giving wasn’t common, masters and their holiday visitors often “tipped” their hats to servants in appreciation of yearlong service and offered monetary gratuities to servants during Christmas. Though a household custom, “tipping” extended to tradesmen and public servants as well. There are interesting accounts of enslaved servants explaining that cash money they possessed was gained honestly by diligently delivering newspapers or tavern serving during the Christmas season. Of course, the extra visiting and feasting during Christmas meant much extra work for servants in food preparation and caring for guests in both their lodging and stabling of their animals. The practice of tipping was by no means universal, in fact, some indentured and slave masters opposed the practice: in 1774 Virginian Landon Carter penned a diary entry noting satisfaction in “not letting my People keep any part of Christmas.” Scrooged again.

Costumed “Mumming” faded from popularity about the time of the Revolutionary War, when some sullied the traditional festive and charitable purpose. Instead of offering plays, songs or prayer; mumming thugs burst uninvited into homes with demands for food, drink and money under threat of committing mischief, damage, or bodily harm. This menacing mockery of the original playful and charitable intent doomed Mumming until it was revived much later as a Halloween children’s activity.

More Christmas Traditions

One supposed symbol of colonial Christmas spirit doesn’t quite hold up. Originally grown in South America, the pineapple was already cultivated in the Caribbean when Columbus arrived, soon declaring pineapple the most delicious fruit in the world. Its relatively long shelf life made it invaluable for medicinal purposes, particularly in preventing scurvy aboard ship, even when dried, candied, or floating in Madeira. The pineapple, first grown in Europe under glass at the Dutch Royal Botanical Gardens in 1680, was brought to Royal English hothouses by William of Orange about 1688. It was quickly associated with health and royal favor; for to know pineapple meant you had powerful associations to royalty.

In America, pineapples were incorporated as furniture décor, carved over hearths and lintels as a symbol of welcome and generosity, but actual, live pineapples were rare and extremely expensive. So much that they were often not eaten, but rented out to serve as centerpieces at social galas. Stories survive of a single pineapple making the rounds at successive Williamsburg homes as a focal curiosity and social status symbol for the proud host-mistress. Problematically for this alleged Christmas tradition, pineapples did not ripen until February through April and do not continue to ripen after being picked. Thus, any supposed pineapples on Christmas display in colonial Savannah, Charleston, or Williamsburg were either underripe and very “green,” or wooden carvings.

Although we modernly think of fruit adorning wreaths as a colonial Christmas tradition, fruit was an expensive and precious resource, especially in maintaining health through winter, and could not be wasted as ornamentation. In fact, there is no evidence that wreaths were displayed in colonial America. Similarly, candles were not only expensive and tedious to make, but a risky fire hazard: any candles in windows would have been for pragmatic reasons rather than celebration; and closely guarded.

Colonial Christmas traditions, like mumming, dancing, caroling, firing guns, were focused on adults, rather than children. Bear in mind that before the American Revolution, “Santa Claus” did not yet exist in America. Clement Moore’s “A Visit From St Nicholas” (“Twas the night before Christmas…”), based on an obscure Dutch fable that had not yet achieved popular notoriety in America, was not published until 1823. Similarly, the first Christmas tree displays did not appear in America until the mid-1840’s.

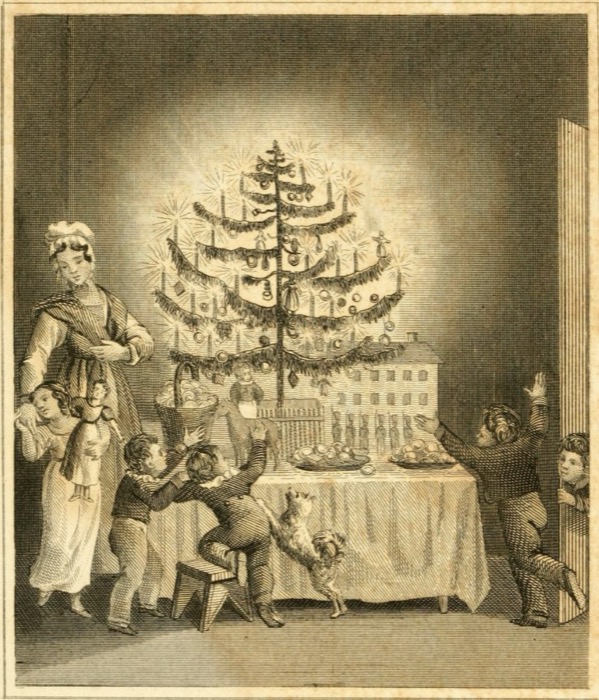

The first popular documentation of a Christmas tree was an illustration in the book “The Stranger’s Gift: A Christmas and New Years Present,” published in 1836 (see image at the top of the article), which tells the story of German emigrants, “strangers” to most British-origin Americans, with the hope that German emigrants would be accepted into American society. Its “gift” was an invitation for Americans to share German Lutheran Christmas traditions, with the Christmas tree tradition illustrated in the book. According to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the first documented Christmas tree, at least in Virginia, was erected by German immigrant Charles Minnigerode in 1842 Williamsburg (although German immigrants likely had private trees before that).

Conclusion

In the late 1800’s, after the Civil War, popular books like Washington Irving’s “The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon” (1819) and Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” (1843) told stories of the gracious redemption of Christmas. With recognition of the redeeming Christ Child as God’s gift to man, the focus of Christmas shifted from adults to children, from ribaldry to generosity. Even as secular symbols of Christmas became more popular, that popularity elevated Jesus’ birth as the beginning of the Greatest Story Ever Told and encouraged church reintegration of Christmas into the calendar of Holy Days. Which is what we mean as “Holiday,” which we should keep every day, and all year long, as Tiny Tim’s plight eventually convinced Mr. Scrooge to do in 1843.

TOP PHOTO: The German Christmas Tree tradition illustrated in “The Stranger’s Gift,” 1836. (The Library of Congress, Internet Archive )