Summary: With Spain officially joining France on America’s side and the Netherlands also aiding the cause, the global conflict that was the Revolution was heading to a climax.

RECAP: Part 1 of this series discussed the covert support provided by France, Spain and Holland prior to France entering into an open alliance with the “United States of North America,” as the treaty of alliance described us. Part 2 focused on the “Bourbon Alliance” between the cousins Louis XVI of France and Carlos III of Spain and their preparation for overtly committing to the American Revolution, and the impact of the French Alliance. This conclusion presumes you’ve read parts 1 and 2 as our gaze shifts to the last four years of the Revolutionary War, from 1779 to 1783, focusing on Spain and the Netherlands who willingly or unwillingly joined the conflict.

Spain Enters

In April 1779, with the largest treasure fleet in Spanish history finally arrived from Mexico, and 9,000 troops safely returned from Argentina, Spain signed a secret formal alliance with France. Two months later, on 21 June, Spain declared war on Britain, openly joining the American Revolution as a formal ally of France. Spain did not want to be bound by the French – American alliance which required all parties to make a joint peace with Britain. Spain had her own goals to fulfill, but did agree not to make peace with Britain until they granted American independence; an agreement that would require separate peace treaties at the war’s end.

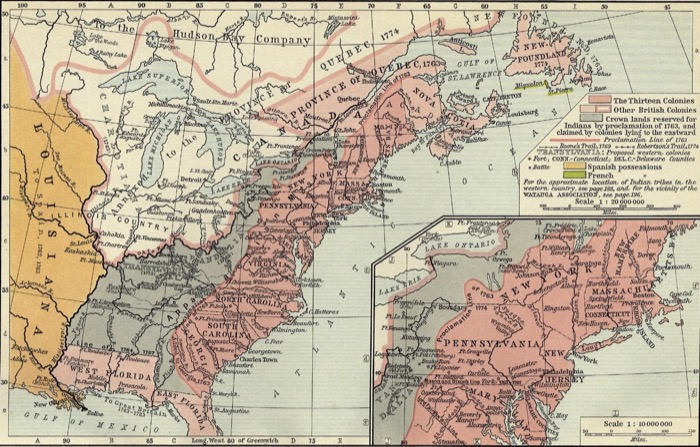

Spain wanted to regain territory lost to Britain in the Seven Years’ War, including the island of Menorca in the Mediterranean and Florida. She also wanted to drive Britain from South America, where a British alliance with Portugal, as well as toeholds in Guatemala and Guyana, threatened Spanish silver mining and her annual treasure fleets. Spain and France agreed to carry out the Bourbon strategy: uniting their fleets against Britain to claw back territory and maintaining a constant threat of cross-channel invasion; which the British had to defend against, weakening her forces elsewhere. But, Spain insisted, the most important task was to retake Gibraltar from the British.

The Rock of Gibraltar is a large crag 1,400 feet high on the southern tip of Spain overlooking the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow channel connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic. In ancient times Gibraltar was known as the northern half of the “Pillars of Hercules.” Together with its twin peak on the African side, the Pillars were known to the ancient Phoenicians, Egyptians, and Greeks as the western edge of the known world. Modernly, we recognize the Rock as the Prudential Insurance Company’s symbol of solidarity. In the 18th Century “Age of Sail” and “Great Empires,” Gibraltar was strategically critical to control of the Mediterranean.

France reluctantly joined Spain in a siege of Gibraltar which began 24 June 1779. The Gibraltar siege isolated British forces on the Mediterranean isle of Menorca, which the French and Spanish retook after a five-month siege then turned their full attention to “the Rock.” It consumed vast resources from both France and Spain, over 60,000 troops, 50 ships of the line and floating artillery batteries. It spawned a host of naval battles nearby as British fleets were diverted from American tasks to repeatedly reinforce and resupply Gibraltar by breaking through the Spanish-French blockade.

Despite the costly investment, the siege could not dislodge the 7,500 British defenders who began tunnelling into the limestone Rock, eventually creating a labyrinth of defenses and hidden gun positions. Lasting three years, seven months and 14 days until February 1783, at a cost of 1,500 British combat deaths, over 6,000 Spanish and French combat deaths, and countless losses on both sides to wounds and rampant disease, Gibraltar became the largest, longest and bloodiest battle of the American Revolution. Like many Americans in 1783, many historians believe the British lost America because of naval and materiel resources diverted to support Gibraltar.

Galvez Shapes America

Beyond Gibraltar; Spain engaged Britain around the globe. In naval battles in the Caribbean, capture and loss of sugar islands, trading posts in Africa, and confrontations in Malaysia and the Orient, Spain was successful elsewhere; in critical ways that shaped the formation of our nation.

When Spanish governors of Louisiana began shipping military goods from New Orleans up the Mississippi to Louisville and Fort Pitt in 1775, the flatboats passed right by British forts on the east bank of the river at Manchac (Fort Bute), Baton Rouge, and Natchez (Fort Panmure); who were powerless to interdict the contraband without risking war with Spain. After Spain entered the war in 1779 the situation changed; British forts prevented Spanish and American goods from sailing the river. Governor Galvez also learned of the British planned attack on New Orleans.

To neutralize those threats, Galvez raised a small army of about 1,200 including 520 men of the Spanish Fixed Regiment, Acadians, natives, Creole adventurers, current as well as former enslaved, and about a dozen Americans commanded by Oliver Pollock (creator of the dollar sign). Evading detection by trudging through bayou country, Galvez captured all three Mississippi forts and then, in 1780, turned his focus east along the Gulf coast.

The British bastion at Pensacola was the “Gibraltar of the Gulf of Mexico;” the home port for the British fleet of 26 ships of the line that patrolled the Gulf; threatening Spain’s treasure fleets and silver-mining colonies on the Gulf’s perimeter. Pensacola mounted large guns whose range exceeded that of most shipboard cannon, and its stone walls seemed impervious to shot. To take Pensacola by land, Galvez first had to capture Biloxi, then took Fort Charlotte, in Mobile, by siege. Spanish forces then dug in for the expected British counterattack.

While they waited, back in Spain spies had relayed word of a massive British supply convoy about to depart Britain. In addition to five East India Company ships transporting military supplies destined to fight the French in India, the remaining 63 ships, destined for America, were carrying 80,000 muskets, 294 cannon, military equipment and uniforms for 40,000 troops, a fresh army of 3,144 men, and just over £1 million in gold and silver coin (modernly, about $13 Billion). The intelligence included not only when the convoy was scheduled to sail, but its planned route of travel.

The Spanish squadron hastily dispatched to intercept almost tripped on the convoy about 150 miles off the west coast of Spain on 9 August, 1780. The encounter is known solely by the date as “The Action of 9 August 1780.” Mimicking British signal lanterns in the rigging, the Spanish tricked the convoy into believing them to be British escorts. The convoy did not realize the danger until too late. Half the British escort ships, surprised and outmatched, fled. After a brief fight, without a single casualty, the Spanish captured all but eight of the merchant ships intact and incorporated the captured warships into their navy. It was the greatest British maritime loss of the war, sending shockwaves through the maritime insurance industry throughout Europe.

King George III, who had invested heavily in East India Company stock, fainted when he got the news. British popular support for the war, and confidence in Parliament, plummeted. News of the coup reached Congress almost simultaneously with news of the victory at King’s Mountain; a victory that would have never happened had that British fleet reached America.

Back on the Gulf coast… After surviving the British counterattack on Mobile, Galvez attacked Pensacola by both land and sea, slogging through swamps and bayous to gain access, then personally sailing aboard the lone Spanish ship able to breach Pensacola’s harbor. After a three-month siege, on May 8, 1781 a lucky Spanish cannon shot hit the British powder magazine inside the fort, killing about 100 soldiers and leaving only a scarce supply of gunpowder; forcing the British surrender.

Galvez’ victory set in motion an incredible train of falling dominoes. Without Pensacola the British fleet had no home port in the Gulf, and was forced to withdraw. With the British naval threat removed, the Spanish Gulf fleet deployed forward into the Caribbean, where it took over protection of sugar and spice islands from the French fleet in June 1781. In turn, the full French fleet under the Comte de Grasse was able to sail to the Chesapeake, defeat the British navy at the Battle of the Capes, and prevent Britain from reinforcing Cornwallis or attacking the French troops, supplies, and siege guns sent by sea to Yorktown. Indirectly, Galvez’ series of dominoes enabled the Allied victory at Yorktown.

Britain Attacks the Netherlands

Officially the Netherlands was neutral early in the Revolutionary war. But, more concerned with balance sheets and stock prices than battle wins and losses, the Netherlands had been willing to make loans to Continental Congress when the terms and interest rate were favorable; as they did with all European powers throughout the war. The loans came primarily from private investors, though the government also made substantial loans on terms very favorable to the United States. America relied on those loans to purchase supplies and pay troops. The periodic influx of Dutch guilders, hard silver and gold currency, had helped to maintain confidence in Congress and the value of the Continental dollar.

In 1779 Congress decided to request additional loans from both France and the Netherlands in order to meet the scheduled buy back of the first issue of Continental dollars. They also wanted additional troop and naval commitments from King Louis, and a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the Netherlands. Henry Laurens, former president of Continental Congress, was dispatched to Europe armed with draft copies of agreements for French troops, naval support proposals for loans, and a proposed treaty with the Netherlands. Unfortunately, on his return trip in September 1780, Henry’s ship was intercepted half way across the Atlantic. Before he was captured, Laurens threw his letter satchel overboard, but forgot to add the cannonball. The British recovered everything with a boat hook. In addition to the loan agreements, the British found the draft copy of the potential Treaty of Amity and Commerce being negotiated between Congress and the Dutch. With selective interpretation, Britain opined that Laurens was seeking to violate Dutch neutrality and threw him in the Tower of London on charges of war crimes and treason.

At her foremast and stern post, Andrew Doria flies America’s first flag, the “Continental Union” flag, with the Dutch flag at her mizzenmast. The Continental Union flag featured 13 alternating red and white stripes representing the 13 united colonies, with the “British Union” flag of 1707, also known as the “Union Jack” in the canton. First flown 3 December 1775, before America declared independence, by Commodore Esek Hopkins aboard this flagship in the Delaware River at Philadelphia. Modernly, this flag is generally known as the “Grand Union”, however that name was first used in 1852.

The Continental Union flag was replaced by the Flag Act of 14 June, 1777: “Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” That first Flag Act did not specify how the stars were to be arranged, resulting in many different configurations. There was no standard configuration for the stars until President Taft issued an executive order on 24 June, 1912, establishing six rows of eight stars, with point of each star pointing directly up. In 1959 President Eisenhower signed two executive orders specifying how stars for Alaska, then Hawaii, would be displayed. Since then, on the first day of their term, immediately after inauguration, each successive US president has re-signed that executive order to continue the flag design. (United States Department of the Navy – Naval History and Heritage Command – Phillips Melville, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the fact that Britain herself held multiple trade treaties with the Netherlands; and that British companies were actively borrowing from the Dutch on the same terms offered to Continental Congress, the British determined that Dutch willingness to discuss loans and a trade treaty with America was a breach of neutrality. The decision seemed to violate the British – Dutch mutual defense pact that had been in place since William of Orange had left Holland to become King of England in 1689. It was largely a one-sided agreement which Britain had strained at every opportunity; such that the Netherlands, like most other European nations, was no real fan of Britain. They’d sold gunpowder and muskets to Beaumarchais, allowed Roderigue Hortalez to use warehouses and docks on St Eustatius, and American ships to collect contraband cargoes in Caribbean ports. They’d even fired the first salute to honor an American flag, were the second nation to recognize American independence, and had given neutral port safety to the American sea raider John Paul Jones in Amsterdam, although that was allowed, even required, under international law.

But still, the Dutch had not engaged in any open hostility to Britain and had cloaked all their activity as business. And outwardly business was just, business. …Except that Edward Bancroft, Britain’s spy among the American Commissioners to France, had reported everything; including Beaumarchais’ fake company operations in the Caribbean, the favorable loan rates, and private loans and gifts from Dutch citizens.

By 1779 Britain began retaliating by using false pretexts to board and search Dutch ships, seize cargoes, and impress sailors (the act of forcing them to serve the British crown). Britain was doing so to other nations as well, which caused Russia to form a “League of Armed Neutrality.” Established by Catherine the Great to bind neutral countries together against violations at sea by the British navy, the members pledged united military response against any belligerent who interrupted neutral trade. In theory the might of the Russian military would halt British transgressions. In December 1780, when the Netherlands stated intent to join the League of Armed Neutrality, Britain preempted Dutch membership by using Lauren’s papers as an excuse to declare a surprise war.

It was an opportune and calculated move by the British. They risked war with the League members, particularly Russia, Denmark and Sweden, but could always apologize and sue for peace. On the other hand, Dutch colonies were low-hanging fruit. The Dutch military had been savaged during the Seven Year’s War and had not been rebuilt; they had just 20 antiquated ships of the line, most of which were quickly trapped in Dutch ports by a British blockade which was in place by mid-January, 1781.

Evidence suggests that Britain sent orders to naval commanders weeks before declaring war. Within two weeks of Britain’s declaration of war 200 Dutch ships had been taken, with cargo losses valued above 15 million guilders. British warships attacked and captured Dutch colonies in the Caribbean before they received word of war with Britain. In 1781 Holland lost the Caribbean colonies of St Eustatius, Saba, St Marten, Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo. British retribution was exceedingly harsh. In most cases, in reprisal for cooperating with America, the British deported and interned all merchants and foreigners, confiscated all goods on an island, and shipped all to Britain. In 1781 Britain committed 40-plus ships and 11,000 troops to global operations against the Dutch. Ships and troops which were not available to counter Galvez in Florida nor to come to the relief of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Because it took a long time to sail around Africa, Britain’s assault on Dutch holdings in the Indian Ocean began in 1782. Though France defeated a British attempt to take the Cape Colony (modern day South Africa), the Dutch East India Company’s lucrative trading posts in India, Ceylon, the Seychelles, Sumatra, Djakarta, China and Japan were all at risk. Fortunately for the Dutch, the British and its East India Trading company were bogged down fighting French forces in India and could only afford limited forays against Dutch holdings. Still, the Dutch lost the trading colony of Negapatum in India, then surrendered their entire colony on Sumatra (modern Indonesia) to a force from the British East India Company.

The End Game

Now it’s time to return to the two questions posed in Part 1 of this article; What were the last and biggest battles of the Revolutionary War? Those with only a cursory knowledge of events might reply, “The Battle of Yorktown.” However, while this proved to be the decisive engagement in America, it ignores the wider international aspects of the conflict.

After losing Cornwallis’ army at Yorktown in October 1781, the British public forced Lord North’s Tory party from power. The new Whig government, under Lord Rockingham, ordered a cessation of offensive operations in America pending negotiation of a peace treaty. While that ended major battles, there were many more skirmishes in North America, some substantial, as both sides foraged for supplies to hold terrain or towns critical to negotiation strategy. General Washington did not offer a general cease fire to his British counterpart until 19 April, 1783. The last battle of the revolution fought in North America occurred just two days prior, at Spanish Fort Carlos, near the junction of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers (near modern day Saint Charles, Arkansas).

The French-American treaty of alliance stated that the two nations would not make a separate peace with Britain. That agreement was foiled when Spain later entered the war as an ally of France, but did not join the original French-American treaty. France and Spain were still conducting major military operations against Britain, and vice versa, when the United States and Great Britain began peace negotiations. The largest battle of the war, the Siege of Gibraltar, did not end until February 7, 1783. After Gibraltar ended, France and Spain began negotiating separate treaties with Britain. During negotiations, serious fighting continued as each nation fought to gain or hold territory that would be ceded by the treaty. In particular, the French sought to retake the colonies and territory the British had captured from the Dutch. They were largely successful in the effort, but it required confrontations well into the summer.

The last battle of the American Revolution was the Siege of Cuddalore, fought in the Mysore Republic in southeastern India. 12,000 British East India Company and Hanover (Hessian) troops besieged 9,000 French troops and their Mysoran allies. Britain was attempting to recapture a region taken by France earlier in the war. Casualties were heavy on both sides: about 1,500 British and 1,100 French/Mysoran. The siege was accompanied by a naval battle between 15 French and 18 British ships of the line. The French gained the upper hand, driving off the British fleet, which enabled the French commander to unload supplies and reinforce the garrison. The siege continued until 25 July 1783 only ending when the French commander received five-month-old orders to cease hostilities because Britain and France had entered peace negotiations to end the American Revolution.

In the end there were four separate peace treaties concluded among the belligerents of the American Revolution. Britain signed three on 3 September 1783: one with the United States in Paris, and one each with France and Spain at Versailles. The final treaty was between Britain and the Netherlands, who signed a preliminary treaty on 2 September 1783, at Versailles. It was necessary to reach preliminary agreements because the final treaty between France and Britain, to be signed the next day, contained settlement of Dutch territory captured by Britain, then retaken by France, who intended to return it to the Dutch. But, the final treaty between the Netherlands and Britain was not signed until 20 May, 1784.

Because of Britain’s separate declaration of war against the Netherlands, and the separate peace treaties, their conflict is officially known as the “Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.” But there’s no arguing that its root cause and sole reason for Britain’s action was Dutch support for the American Revolution, making it an extension of the Revolution. Even though France recaptured or negotiated for the return of Dutch territory as conditions of their peace treaty with Britain, the Netherlands was the only one of our allies who failed to gain territory during the Revolution, actually losing colonies and trade rights.

Conclusion – The Cost

It’s exceedingly difficult to calculate the costs of any war, but even more so when it was 250 years ago, there were so many belligerents, materials were provided from non-belligerents, and in the middle of the war the principal party invented a new currency – which survives today slightly revamped, but as the world standard. Further, several currencies used by the European belligerents no longer exist. The Euro had no counterpart in the 18th century. The sums, even in 18th century denominations, are massive. Despite the challenges, it’s worth trying to calculate the current value of the aid we got from France and Spain.

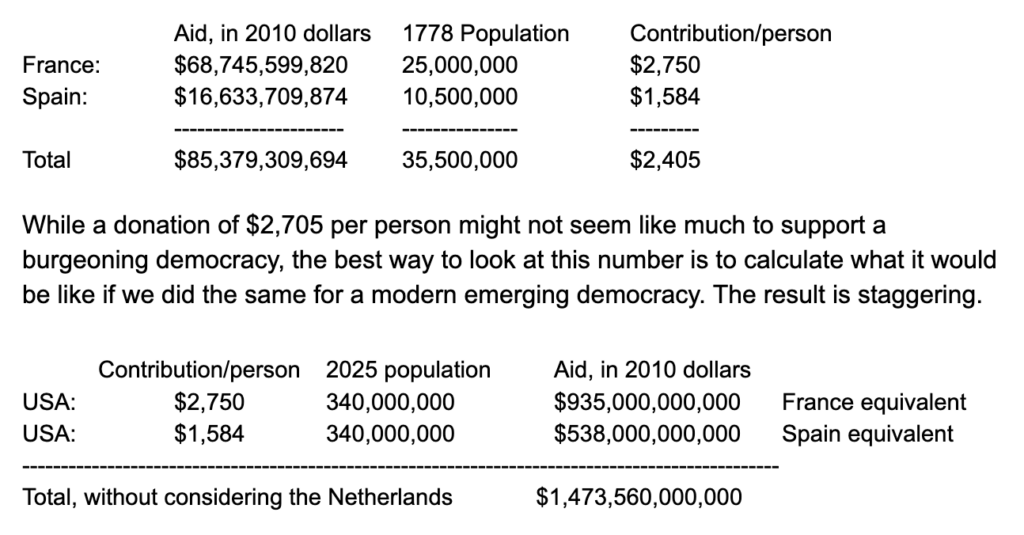

Several financial wizards have made attempts to quantify the value of aid provided to the United States by France and Spain. Larrie Ferreiro, in his book “Brothers In Arms” (pg 339-340; see below for book details), used standard economic growth calculations to “deflate” the relative values of the Dollar, Pound, Livre and Peso. William V. Wenger, in an article for the Journal of the American Revolution (see article details below), took that process to the next level by quantifying French and Spanish aid as a fraction of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from each nation, then used known economic growth to translate the sums into current day value (as of 2010). He calls it the “Economy Cost Comparator,” or “ECC” (Wenger did not calculate Dutch contributions, presumably because most private loan amounts are not available).

Economy cost comparator of aid provided to America, 1775 – 1782, stated in 2010 dollars:

Could we, would we, spend $1.5 Trillion dollars to support an emerging democracy? It’s fantastical to even imagine, yet that’s roughly what France and Spain spent on America. Keep in mind this is just the value of monetary aid, delivered as gifts, loans transformed into war supplies. It doesn’t include the cost of military operations, the war supplies consumed, or the lives invested by our two partners. Is democracy worth it? …Surprisingly, two kings thought so.

TOP PHOTO: The March of Galvez, by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, depicts Galvez’ troops enroute to seize the British forts along the Mississippi in 1779-1780. Galvez’ capture of Baton Rouge and Natchez solidified United States’ control of the continent from the eastern seaboard to the Mississippi river, and prevented British claims to the territory during subsequent peace negotiations in Paris. The following year Galvez turned his attention to Mobile and Pensacola, capturing those strongholds and delivering what was known as West Florida to Spanish control. Spain won the return of East and West Florida during the American Revolution. In 1819 John Quincy Adams negotiated a treaty with Spain for transfer of Florida to the United States and extended the US border through the Oregon territory to the Pacific Ocean.

(Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

You may want to read:

Although the best source and essential for accuracy, poring through primary documents in dusty special collections, or through the National Archives, or simply reading the faded scribbled pages left by founding fathers – none of whom actually wrote in the gloriously engrossed script of the Declaration of Independence – is laborious. All of us are indebted to the writers and thinkers whose work captures, preserves and interprets our founding era. If I’ve teased you into further study, these are good sources to illuminate your understanding of our revolutionary alliances:

Larrie D. Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms: American Independence and Men of France and Spain who Saved It (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016)

Edward F. Butler, Gálvez, Spain—Our Forgotten Ally in the American Revolutionary War: A concise Summary of Spain’s Assistance (San Antonio, TX: Southwest Historic Press, 2015),

William C. Stinchcombe, The American Revolution and the French Alliance (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969)

H.A. Barton, “Sweden and the War of American Independence.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3, July 1966, 412.

Key to Victory: Foreign Assistance to America’s Revolutionary War, by William V. Wenger, 12 April 2021, Journal of the American Revolution

John J. McCusker, How Much is that in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economic History of the United States. (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1992)