Summary: France’s open alliance with America in 1778 transformed the war into a global conflict of grand strategy.

Part 1, “Secret Dalliances,” described the covert support that France and Spain sent to America that began even before the Declaration of Independence was written. At least, it was supposed to be covert, but British spies embedded at Versailles and within the delegation of American Commissioners to France had reported the activity. Aware that at least part of their support was known to the British, France and Spain continued to provide vast supplies of arms, military equipment, and gunpowder to America as surreptitiously as possible. Part 2: Global Conflict, describes the impact of formal alliances, especially that of France, on America’s war with Britain.

The Bourbon Strategy

In 1775 France was the most populous country in Europe and rapidly growing; with about 25 million souls when she declared her alliance with “The United States of North America” in February 1778. It meant that France could field a large army, more than twice the size of the British Army… but size isn’t quality. During the Seven Years’ War (1755-1763) the French army had difficulty standing up to the British except in situations where they held significant numerical advantage, and even then, they struggled. After losing sugar colonies, trade routes to the orient, and all of Canada to the British in the Seven Year’s War, France entered a period of intense military re-tooling.

Military training for officers was emphasized, ineffective leaders were purged, and discipline was enhanced. The army undertook a massive effort to lighten soldiers’ loads to make them more mobile and effective on the battlefield, and arms were redesigned to make them not only lighter, but simpler and more effective. Muskets built on older patterns were retired and replaced with newer designs (which is why France had so many surplus muskets to send to America). The result was a slightly smaller French army that was better trained and more mobile.

But; that army was primarily designed for battle on the European continent. It couldn’t be brought to bear against Britain without an effective navy; or one at least as effective as that of the British, which separately, the Bourbon cousins Louis XVI of France and Carlos III of Spain lacked. Islands are notoriously difficult to invade. Other than William the Conqueror of Normandy who had settled down and turned British after conquering England 700 years previously, neither France nor Spain had ever successfully invaded Britain. France’s naval upgrade lagged. She needed more and better trained sailors; and faster, more agile vessels which carried heavier “throw weight” – more guns of heavier caliber.

During the Seven Years’ War France had set a goal of 80 “ships of the line” to achieve rough parity with Britain’s modern navy of 64. Although she built nine of those modern vessels, the loss of Canada and Spanish takeover of Louisiana’s administration meant France had little to defend in the new world. As her military focus shifted to continental Europe, where a navy was not essential, France’s fleet dropped below sixty ships.

Though the American colonies’ declaration of independence from Britain in mid-1776 opened the door to active intervention in North America, France’s Foreign Minister, the Comte de Vergennes, knew that France and Spain could only achieve maritime parity by combining their fleets against Britain, a key point of Bourbon strategy.

Spain wasn’t ready. Spain was preoccupied with securing its South American interests against Portuguese border claims along the Argentine and Uruguay borders. Though relatives also occupied a throne in Portugal, the relation was marital. King Jose I of Portugal was married to Mariana Bourbon; King Carlos of Spain’s sister and cousin to Louis of France. Under Jose’s Despotic first minister, Marquis de Pombal, the small nation was aggressively seeking territorial expansion in South America. Since Pombal lacked the military power to consolidate the gains, Portugal was looking towards Britain, her ally during the Seven Years’ War, to back her not-so-subtle encroachment into Spanish silver territory.

With Britain already expanding in Florida, Guyana and Guatemala, Spain’s Foreign Minister, el Conde de Floridablanca, needed to quickly snuff Portuguese ambition. He sent 9,000 troops to Buenos Aires to enforce the border, protecting the sluggish convoy by diverting precious ships of the line previously designated to escort the massive treasure fleet slated to depart Mexico in 1777. With a horde of freshly-minted silver pesos worth $50 Billion in current money, the richest Spanish treasure fleet in history was indefinitely delayed. Now vulnerable in two critical colonial arenas, short on ships and cash-flow disrupted, the moment wasn’t right to challenge Britain directly. Floridablanca had to keep Britain focused elsewhere.

The Bourbon strategy required a combined fleet to challenge Britain’s naval dominance, and Spain’s was still rebuilding; constructing 30 new ships of French design so that the two fleets could combine more effectively. Equally important, both Bourbon cousins needed to reinforce their global colonial defenses before openly confronting Britain. They needed a distraction; and they needed time. They bought both by investing in revolution.

Buying Time

For two years France and Spain supplied Americans with the military material necessary to engage the British; and the strategy paid off. Beaumarchais’ fake trading company, and others, kept up a steady stream of military supplies from France, and his Spanish counterpart, Diego Gardoqui, maintained a stream of cash from Spain channeled through Havana (Gardoqui’s financing was so critical to the war effort that George Washington later invited him to stand at his left side during his first inauguration). By the end of 1777 Britain had committed over half her military power fighting to retain her North American colonies, sending nearly 75,000 troops to continental America or bolstering the Caribbean sugar and spice islands which American privateers were so fond of raiding. These experienced troops were drawn from other colonial possessions, replaced with raw recruits or not at all.

Over half the highly trained Hessian troops available to George III, which had complicated past European conflicts by creating an annoying British stronghold in central Europe, were committed in America. From the view of France and Spain, every soldier, every bullet expended in America weakened Britain. With Washington’s narrow defeat at Germantown and the capture of an entire British army at Saratoga, Vergennes, and his Spanish counterpart, Floridablanca, assessed the Americans as capable of fighting a protracted war. In fact, Vergennes’ greatest fear was that the British would come to the same conclusion and realize that their smartest move was simply to end the war on friendly terms, swapping exclusive trading rights with America in exchange for independence and peace. Vergennes thought the timing for France was now or never.

Still, Spain wasn’t ready: that massive treasure fleet of $50 Billion in silver pesos was finally about to depart Mexico, and the 9,000-man army that had cowed the Portuguese into submission in South America was about to return home. Neither convoy was sufficiently defended to cross the Atlantic if war with Britain broke out, and Spain could not afford to lose either. Even as Floridablanca angrily argued for delay, Vergennes knew France could no longer wait, signing an alliance with the United States on 6 February 1778.

Open Alliance

France waited five weeks to inform the British Secretary of State of their Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States, presenting a copy in London on 13 March. France did not provide a copy of the military alliance treaty with America. It was important for France that Britain fire the first shot so that France could claim a defensive war and call upon her allies for support.

Vergennes got his wish on 17 June, when a squadron of British ships fired upon a lone French vessel sailing in international waters, inflicting heavy casualties. Vergennes used the delay to prepare, sending word to colonies in South America, Africa, the Mediterranean, Middle East, India, Indonesia and China: be prepared for war with Britain. He carefully worded warnings to French allies the Ottoman Empire and to Russia – who were mutually engaged in a smoldering brinksmanship which Vergennes was trying to mitigate before it became open conflict. By plausibly claiming a defensive war, French treaties with the Ottomans prevented them from assisting Britain.

Likewise, Catherine the Great assessed that American independence was favorable to Russian interests, and repeatedly declined British requests for troops and monetary aid. The European world was politically complex, still is, but, with the exception of George III’s Hanover electorate (the Hessian principalities which George ruled in what is now Germany), almost no one on the continent was a fan of Britain.

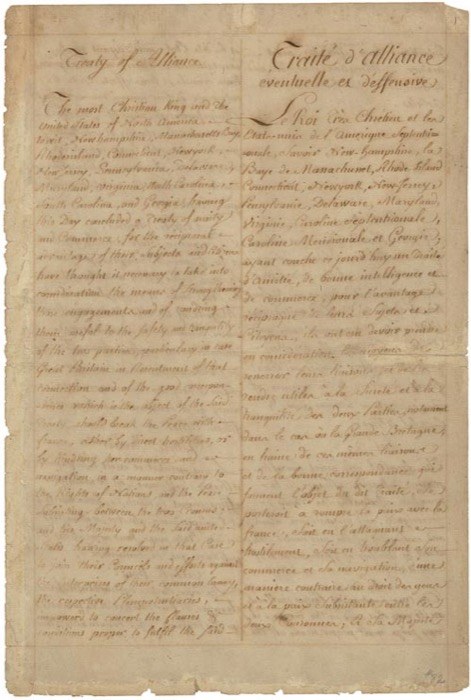

(Perfected Treaties, 1778 – 1945; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. – Treaty of Alliance with France (1778) | National Archives )

Effects of Globalization

Of course, British spies had sent notice of the French-American treaties even before they were signed. France’s entry into the war transformed it into a global conflict of grand strategy; which forced Britain to re-allocate critical resources away from America. Britain had to protect her colonies scattered around the globe, and to reinforce the British East India Company’s defenses in India, Africa, and Asia where they were in close competition with the French and Dutch East India companies.

Globalizing the Revolution had an immediate effect in America. Just as Vergennes had feared, the British sent a delegation, the “Carlisle Commission,” to offer peace terms to the colonies, including self-rule for the colonies and seats in Parliament. But Congress, confident in their new alliance with France, held out for full recognition of American independence. Even as they were talking, Britain recalled a dozen ships of the line and 6,000 troops from America to reinforce other at-risk colonies; which forced the withdrawal of the British army occupying the second-largest English-speaking city in the world – Philadelphia.

General Washington brought his newly trained Continentals out of winter quarters at Valley Forge to attack the Redcoats as they marched towards New York City. The sharp battle at Monmouth, NJ, on a June day so hot that more men fell from heat exhaustion than musket balls, demonstrated the new confidence of American troops. With American insistence on independence, the loss of Philadelphia, and the perceived tactical defeat at Monmouth, the Carlisle Commission returned to Britain a failure.

Britain was forced to withdraw ships from the American theater to protect her home islands against threat of French invasion across the English Channel. In July French and British fleets, more than 70 ships altogether, fought off the isle of Ushant (Ouessant, in French) at the southern mouth of the English Channel, resulting in 1600 casualties. The battle demonstrated the very real threat of French invasion or coastal raiding, and Britain recalled additional colonial troops and ships to defend the home isles.

In America the effect was pronounced. In August 1778 a French squadron under command of Admiral Comte d’Estaing arrived off Rhode Island to land troops and provide a naval blockade to drive the British from Newport. In addition to ships and troops, d’Estaing also brought another loan of 3 million livres (about $6 billion today). While this first attempt at allied operations turned for naught due to communication issues and untimely storms, it laid the seeds for future coordination. The French were in America, and fully in the war.

France maintained a force of at least 5,000 troops in America through the rest of the war, surging at opportune moments; forming at least a quarter, at times nearly two thirds, of Washington’s main army and supporting operations in the Carolinas and Georgia. At the decisive battle of Yorktown, where American troops numbered about 6,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia, the French provided 11,000 troops, 29 ships of the line, around 80 transports and all of the critical siege guns – a presence so overwhelming that British General Charles O’Hara, standing in for the devastated General Cornwallis, initially offered his sword to French General le Comte d’ Rochambeau, who graciously re-directed the surrender to Washington.

With France’s open support the shipment of war material to America became a flood of goods guarded by the French navy. Over the course of the war France, Spain and Holland sent America nearly 250,000 muskets, enough uniforms and material to clothe at least 400,000 soldiers, over a million pounds of gunpowder (much of it Dutch), more than 500 bronze cannon, and countless deliveries of tools, tents and the implements of war.

As we will see next time, in the conclusion to this series, the modern value of French aid is nearly a trillion dollars. Most important to our independence was French commitment of ships and troops – lives – to battlefields not only in America, but from Guatemala to the Mediterranean, South Africa, India, and Indonesia, drawing British troops and ships away from America.

Next Time

In the conclusion to our Revolutionary Alliances series we will welcome, at last, Spain’s entry into the war including how it reshaped our western border; how The Netherlands became our final undeclared ally of the Revolutionary War; and a valuation of France and Spain’s support.

TOP PHOTO: The naval battle of Ushant, 27 July 1778. French ships flew the Bourbon ensign at their masthead, a white flag with the Fluer de Lis. 60 capital ships of the line and numerous smaller ships were involved. The battle sounds could be heard 100 miles away, in both Britain and France, a reminder that invasion of Britain by France was a real threat and forcing Britain to recall ships and troops from America for defense. (Théodore Gudin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

You may want to read:

Although the best source and essential for accuracy, poring through primary documents in dusty special collections, or through the National Archives, or simply reading the faded scribbled pages left by founding fathers – none of whom actually wrote in the gloriously engrossed script of the Declaration of Independence – is laborious. All of us are indebted to the writers and thinkers whose work captures, preserves and interprets our founding era. If I’ve teased you into further study, these are good sources to illuminate your understanding of our revolutionary alliances:

Larrie D. Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms: American Independence and Men of France and Spain who Saved It (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016)

Edward F. Butler, Gálvez, Spain—Our Forgotten Ally in the American Revolutionary War: A concise Summary of Spain’s Assistance (San Antonio, TX: Southwest Historic Press, 2015),

William C. Stinchcombe, The American Revolution and the French Alliance (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969)

H.A. Barton, “Sweden and the War of American Independence.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3, July 1966, 412.

Key to Victory: Foreign Assistance to America’s Revolutionary War, by William V. Wenger, 12 April 2021, Journal of the American Revolution

John J. McCusker, How Much is that in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economic History of the United States. (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1992)