Summary: The secret military material assistance provided by France and Spain early in the war was vital in America’s fight for independence.

Teaser:

Americans were quick to fight for their liberties, but once the shooting began, they realized they were up against a powerful, disciplined, professional enemy. Our founding fathers immediately realized we needed help. We are particularly myopic on this aspect of our national birth. France, Spain, and to a lesser extent, The Netherlands were not just midwives, but also provided the expensive shears needed to sever our umbilical relationship with Britain. This two-part article looks at how those birthing bills were paid.

As you read, consider two questions:

- What was the largest battle of the American Revolution?

- Where was the last battle of the American Revolution fought?

Opening Salvoes

When “the shot heard round the world” was fired on Lexington Green (250 years ago on this April 19) rebellious Americans had a very limited goal: liberty. At least that’s what they said. What they meant was recognition of rights under the British constitution, with equal representation in Parliament foremost among them: a say in the laws that governed them. “No taxation without representation” could be solved if each of the 12 colonies (since Delaware had not yet split from Pennsylvania) had ministers in the House of Commons and peers in the House of Lords.

Many Americans looked to King George III, who they believed sympathized with their plight, to force Parliament to repeal some of its odious laws and to rectify the lack of colonial representation in Parliament. Prominent among those was John Dickenson, a Continental Congressman from Pennsylvania. Shortly after the horrible carnage at Bunker Hill, on July 5, 1775, Dickenson wrote, with the approval of the second Continental Congress, what became known as the “Olive Branch Petition.”

Using conciliatory language with “tender regard” from “faithful subjects” to “our Mother country,” Dickenson petitioned King George to intervene with Parliament on behalf of American colonists, stressing that Americans were loyal to the King; their anger was directed at Parliament for the perceived curtailment of constitutional rights which left Americans no option but to arm themselves and resist the imposition of Parliamentary tyranny. It was a last-ditch effort to avoid war with Britain.

Signed by all Continental Congressmen present, the “Olive Branch Petition” was rushed to London by the fastest ship available and officially presented to the Crown by emissaries Richard Penn and Arthur Lee on 1 September, 1775. The next day Penn and Lee sent a succinct report to Congress: “we were told that as his Majesty did not receive it on the throne, no answer would be given.”

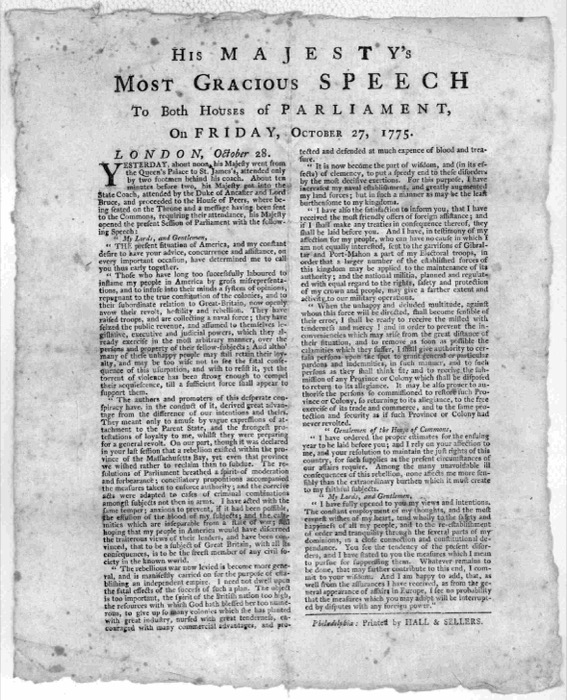

George’s apparent reply came in an address to Parliament on Friday, 27 October, 1775. It was not the speech that Americans hoped for. Instead, George declared the Americans to be in open rebellion; ungrateful, unhappy, and deluded rebels in quest of “establishing an independent empire.” George declared he would send Hessian troops and called on Parliament to send an army and navy to America to crush the revolt. Destined to arrive in America in July, 1776, it would be the largest force ever deployed to that point in history.

Common Sense

George’s speech, printed in British papers the next day, took almost 13 weeks to reach America, then was reprinted in Philadelphia just as Continental Congress resumed session in mid-February 1776. Before that, Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” pamphlet was printed in January. It was widely read and extremely influential in its advocacy for independence (still printed today and remains the all-time best-selling American print title). When the King’s speech arrived, revealing that George III was NOT going to help Americans and was fully backing Parliament… many Americans realized that declaring independence was just “Common Sense.”

In Congress, a primary reluctance to declaring independence was the stark reality of America’s inability to defeat Britain without foreign help. Although rich in farmers, America lacked trained soldiers and guns, cannon, gunpowder, military supplies of all sorts, and money to buy them. Supplies had to come from abroad, and we needed a navy to secure transport across the Atlantic. Some Congressmen believed that America had to secure alliances with foreign powers BEFORE declaring independence. Others, led by John Adams and the Virginia delegation, argued that as long as America remained a colonial possession of Britain, and the war was about British rights, no foreign power would intervene: only by declaring independence could America negotiate for treaties of commerce, using her agricultural commodities to lure trading partners – and military allies.

Tired of endless debate, on May 19 Virginia, the geographically largest and most populous of the rebelling colonies, declared independence from Britain; then challenged the rest of the colonies to follow suit. Cognizant of the desperate need for foreign aid, three weeks before voting for independence on July 2nd Congress formed a committee to draft proposed “Treaties of Amity and Commerce” to lure foreign partners.

But… foreign partners were already secretly planning assistance. France and Spain had lost colonies, trade routes and national pride to the British during the Seven Years’ War (1755-1763). The two countries already had a joint secret strategy, if not a formal alliance, against Britain in place. Both were anxious for revenge against Britain, perhaps with opportunity to recoup some of their losses, and were happy to use America as a surrogate to do so. But neither were ready for open warfare with Britain nor willing to declare an alliance until America proved itself capable of waging a protracted war. To do that, America needed an immediate influx of military supplies.

Although multiple agents in France and Spain soon began an arms race to covertly supply America, the first to create a steady stream of desperately needed military supplies was Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, famous playwright (The Barber of Seville, Marriage of Figaro) and covert French spy.

(Jastrow, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Roderigue Hortalez and Compagnie

Working clandestinely with Connecticut merchant Silas Deane, a Continental Congressman secretly assigned to obtain supplies as one of the American Commissioners to France (with Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee), by late 1775 Beaumarchais convinced both King Louis XVI of France and King Carlos III of Spain to secretly support America.

Using a million livres of Louis’ seed money, Beaumarchais founded a fake Spanish trading front, “Roderigue Hortalez and Compagnie,” to channel arms and supplies to America. Deane agreed America would pay for the goods with shipments of “good Virginia tobacco,” flax, hemp, and indigo. If discovered, it would outwardly look like a legitimate trading exchange. The French government quietly transferred surplus French .69 caliber Charleville and St Etienne muskets left over from the Seven Years’ War to Beaumarchais’ warehouses along the coast; as well as surplus cannon, tents, uniforms, and all sorts of military equipment provided by France and Spain.

Before the Declaration of Independence was even drafted, Beaumarchais had arranged for an initial shipment of 27,000 muskets, 200 bronze cannon, cannonballs, 20,000 pounds of gunpowder, mortars, tents and enough clothing for 30,000 men to be shipped from France to the Dutch colony of St Eustatius, in the Caribbean, where it was re-shipped it to American ports.

Beaumarchais’ covert supply line to America would have been incredibly remarkable if not for the fact that Edward Bancroft, who had once been a student of Silas Deane in Connecticut, and who had been unwittingly recommended by Benjamin Franklin to become Deane’s personal secretary in France, was a British spy. Bancroft provided intimate details of Beaumarchais’ operation to the British, who decided not to intervene to avoid open war with France and Spain – and to avoid revealing they had a spy embedded among the American Commissioners to France.

By 1777, about 18 months into its operations, Beaumarchais’ operation was hopelessly compromised and ceased pretention to secrecy. In a classic case of spy vs. spy “I know that you know that I know that you know,” France continued to ship arms through Roderigue Hortalez to focus British attention there… and not on the multiple other companies covertly smuggling arms to America. While it was no secret that French and Spanish arms dealers were supplying America, being paid with millions of livres, pesos, and guilders from the French, Spanish and Dutch treasuries, the British were ineffective at interdicting the flow.

The greatest flaw in this arrangement was not in France or Spain, but in America. Much to our continuing embarrassment, or perhaps at this point 250 years later our blissful ignorance, we never sent the hundreds of shiploads of “good Virginia tobacco,” nor any other goods, promised by our Commissioners to France as payment for this vast covert flow of munitions and supplies.

By the end of 1776 Beaumarchais had arranged cargoes for over forty ships, not only of French, Spanish and Dutch equipment, but massive quantities of Dutch gunpowder and saltpeter; a flow of arms which began to have significant impact in America. Archeologically, over half the musket balls recovered at the Trenton and Princeton battlefields were from .69 caliber arms, revealing that by Christmas, 1776, Washington’s main army was primarily equipped with supplies shipped from France and Spain (British and Hessian “Brown Bess” and Potsdam muskets were .75 caliber).

Then, in mid-March, 1777, after seven weeks at sea, the “Mercure,” first of five Roderigue Hortalez’ ships, arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, delivering enough arms, uniforms, equipment and precious brass cannon to fully equip a 30,000-man army. Muskets and gunpowder were distributed to militias in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Cannon were remounted on their freshly painted Spanish-red carriages and sent to the front. The first arrived near Saratoga on 26 July, just as Horatio Gates was digging in his Northern Continental Army in faint hope of repulsing the British invasion led by General “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne.

By August the newly arrived muskets and powder equipped John Stark’s New Hampshire troops, who, along with the Green Mountain Boys and Massachusetts militia, decimated or captured almost two complete Hessian regiments at the Battle of Bennington. On the heels of that success, freshly armed with their Charleville muskets, New England militia flooded to Saratoga, providing Gates with an additional 6,000 fresh troops and a more than 2-to-1 numerical advantage over his opponent. In the two ensuing battles the newly armed Americans inflicted complete defeat on Burgoyne, killing or capturing his entire 7,200-man army at a cost of 90 Americans killed, 240 wounded.

Saratoga signaled an end to the battlefield equipment dominance enjoyed by the British. That winter at Valley Forge another recently-arrived foreigner, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, would provide American farmer-soldiers with the training and discipline necessary to defeat a professional army. Saratoga proved to the French that, properly armed, America was capable of waging a protracted war. On February 6, 1778, France signed two treaties with the “United States of North America”: a Treaty of Amity and Commerce, and, at last, a Treaty of Military Alliance.

Assistance from Spanish Louisiana

Not only was Spain providing military arms and equipment to America in conjunction with the French, Spain was sending arms directly to ensure that British troops remained entangled in North America. Spain had its own entanglement in South America, where it was engaged in a smoldering skirmish with Portugal over the borders between Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. Portugal and Britain had a loose alliance, and Spain wanted to keep Britain’s priorities on “America Norte” so that Britain did not interfere with Spanish priorities in “America Sud.”

Starting in late 1775 the Spanish Governors of Louisiana, Luis Unzaga (1769-1777) and his successor, Bernardo Galvez, began shipping Spanish arms up the Mississippi to Louisville (in Kentucky county of Virginia) and Ft Pitt – modern day Pittsburg (which was then in territory claimed by both Virginia and Pennsylvania). Continental Congress, through their chief financier Robert Morris, assigned a transplanted Irishman named Oliver Pollock to represent America to the Spanish in New Orleans. Shortly after George Washington discovered that there were only 38 barrels of gunpowder for the entire Continental Army to fight the siege of Boston – less than half a pound per available musket, Unzaga declared 10,000 pounds of Spanish gunpowder in New Orleans as “surplus” and arranged for it to be auctioned for pennies on the peso to Pollack’s agents; who immediately shipped it up the Mississippi to eagerly waiting Americans.

King Carlos, and his able-bodied minister the Conde de Floridablanca, approved of the deeply-discounted sales of surplus arms left over from the Seven Years War in exchange for more of that “good Virginia tobacco.” And, unlike the Commissioners in France, Pollock maintained accurate accounting records and ensured that tobacco payments to Spain were sent either down the Mississippi or, predominantly, from America’s east coast to Spanish ports in the Caribbean. It wasn’t long before surplus gear was supplanted by new equipment and uniforms made under contract in Spain, then shipped to Havanna, the seat of Spanish power in the new world. From there goods went to the capital of Spanish Louisiana, New Orleans, where the governor sent it upriver under the protection of the Spanish Regiments.

Spanish guns, material and, especially, gunpowder were essential to maintaining American presence at Ft Pitt and frontier outposts and enabled American offensive operations to the west; particularly George Rogers Clark’s expedition to capture Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in 1778, extending American victories deep into Ohio and Illinois territories. The procession of cargo-laden flatboats passed right under the guns of British fortresses on the east bank of the Mississippi at Manchac, Baton Rouge, and Natchez, who could do nothing about it without risking open war with Spain. Only when Spain finally entered the war, not as an ally of America but of France, did the situation change.

Next Time

The above discussion is an over-simplification compressing the international intrigue of the revolutionary period into a, hopefully, entertaining and memorable read. We’ve described the secret military material assistance provided by France and Spain up to the point where they enter an alliance with America. Next time we will look at what happened once our two primary allies entered open hostilities with Britain and will answer those two questions:

- What was the largest battle of the American Revolution?

- Where was the last battle of the American Revolution fought?

TOP PHOTO: Battle of Lexington, 19 April, 1775. Published by John H. Daniels & Son, c. Jan. 15, 1903. (Public Domain, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

You may want to read:

Although the best source and essential for accuracy, poring through primary documents in dusty special collections, or through the National Archives, or simply reading the faded scribbled pages left by founding fathers – none of whom actually wrote in the gloriously engrossed script of the Declaration of Independence – is laborious. All of us are indebted to the writers and thinkers whose work captures, preserves and interprets our founding era. If I’ve teased you into further study, these are good sources to illuminate your understanding of our revolutionary alliances:

Larrie D. Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms: American Independence and Men of France and Spain who Saved It (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016)

Edward F. Butler, Gálvez, Spain—Our Forgotten Ally in the American Revolutionary War: A concise Summary of Spain’s Assistance (San Antonio, TX: Southwest Historic Press, 2015),

William C. Stinchcombe, The American Revolution and the French Alliance (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969)

H.A. Barton, “Sweden and the War of American Independence.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3, July 1966, 412.

Key to Victory: Foreign Assistance to America’s Revolutionary War, by William V. Wenger, 12 April 2021, Journal of the American Revolution