Summary: Women who followed the Continental army filled roles that were desperately needed in the fight for liberty.

Camp Followers in the Continental Army

As Commander-In-Chief of the Continental Army, few challenges vexed George Washington more than “camp followers”: women who followed the army. They represented extra mouths to an army that was always underfed. They took up space in wagons when there were already too few. Most importantly, they were a constant distraction from the discipline, training, and focus required to transform a gaggle of angry farmers into a coherent force capable of defeating the professional British army. In the end, Washington could not have succeeded without them.

The Lesser of Two Evils

Thomas Paine wrote “These are the times that try men’s souls,” but they were equally vexing for soldier’s wives. Women trying to maintain household and family on small farms – which was most of the population – were challenged to bring in crops when their husbands, the main source of labor, were with the army. Townswomen, without the work and wages of their husbands, found it difficult to pay rents in an economy with few waged jobs for women. On the frontier, women left behind when their husband had taken the family musket to join the army found themselves defenseless, even as British instigators rallied natives to join the fight by raiding settlements.

The charity of neighbors suffering the same situation was limited; and all of them were vulnerable to the vagaries of war, crime, and abuses from followers of the “other side;” especially when towns fell to enemy occupiers. Wives of soldiers had to make tough decisions, survival decisions, determining the least bad option. Some were able to move in with family, some with neighbors; but for others survival meant following their husbands in the army.

Already short of food and supplies for troops, and of wagons to move those supplies, General Washington grew dismayed by the number of women and children following the army. He wrote in daily general orders:

“In the present marching state of the army, every incumbrance proves greatly prejudicial to the service; the multitude of women in particular, especially those who are pregnant, or have children, are a clog upon every movement—The Commander in Chief therefore earnestly recommends it, to the officers commanding brigades and corps, to use every reasonable method in their power, to get rid of all such as are not absolutely necessary; and the admission or continuance of any, who shall, or may have come to the army since its arrival in Pennsylvania, is positively forbidden; to which point the officers will give particular attention.”

“…women are expressly forbid any longer, under any licence at all, to ride in the waggons—and the officers earnestly called upon to permit no more than are absolutely necessary, and such as are actually useful, to follow the army.”

To an army that never had enough of anything, camp following represented a significant drain on limited resources. Washington initially tried to ban camp following, but soon realized that camp followers were often the wives of his older, most diligent troops, and if he banned women who had few options, their husbands would desert to care for them.

He also recognized the inequity in a ban. Officers often paid for their wives to spend time in camp and many did. Lucy Knox could not live in occupied Boston, and remained in camp at Henry Knox’ expense after Boston was liberated. Washington had to acknowledge that probably the greatest camp follower of all, who spent every winter encampment with her husband, including Valley Forge, was his own wife Martha. He begrudgingly realized that any decision on camp following was “lose-lose:” if he banned it, he would lose quality soldiers and crush morale. If he allowed it, it cost him rations. Like the women themselves, he chose the lesser of the two evils.

Imposing Structure

As Washington seemingly became resigned to the situation, he urged Congress to make provision for the supplies required to support camp followers. He limited officers’ wives, requiring them to obtain permission to bring wives to camp. He tried to limit the number of camp following wives to about 3% of the enlisted troops (privates and NCO’s) in the army.

Of course, with wives come children. When Washington’s army arrived at Valley Forge in December 1777, he reported 400 women camp followers (just over 2% on the enlisted men, one for every 44 enlisted men). At the end of the war, January 1783, Washington reported 304, or just under 4% of his army’s 7,908 enlisted men, one camp follower for every 26 enlisted men.

More importantly, Washington began imposing rules, regimen and structure on camp followers and gave orders that they be made aware:

“As there is many orders for checking irregularities with which the women, as followers of the army, ought to be acquainted, the serjeants of the companys to which any women belong, are to communicate all orders of that nature to them, and are to be responsible for neglecting so to do.” (General Orders, 8 September, 1777)

Washington’s series of orders, perhaps not deliberately so, ended up creating a sort of “quid-pro-quo” camp following system. In the American army, camp followers were not allowed to sleep in camp but had to set up their own “domestic affairs” elsewhere. Often rules applied, demanding the camp followers set up “outside musket shot” or “cannon shot,” up to 800 yards away. The goal was to protect non-combatants in the event of an attack on the camp.

Women were only allowed to follow the army if they were married to a soldier. If their soldier died, they had 48 hours to clear out of camp (although there were undoubtedly some “marriages of convenience” by women with no other real options). So long as women and children provided some essential service to the army, they drew rations based upon their husband’s rank, could be paid for services, and gained a degree of protection: in 1779 Private Ezekial Adams of South Carolina received 35 lashes for abusing his wife.

Essential Service Rendered to the Army

Services included laundry, which, given the hygiene and disease that challenged the army, was truly “essential.” In an army where men were often, if not usually, issued fabric to make their own uniforms and clothing; sewing, tailoring, knitting and darning were essential tasks. Collecting and chopping wood was another ceaseless task. Probably the most important, but least remarked service, was answering the constant demand for water. Using a wooden yoke across their shoulders which carried a thirty-pound bucket on each end, women constantly hauled water from source to camp sites.

Nursing was also important, and was a paid position for some women: because of the rampant risk of serious disease, nurses earned eight Continental dollars per month (as compared to a private soldier’s pay of six and two-thirds Continental dollars per month). During and after battle, everyone was expected to pitch in: camp followers were tasked to guard wagon trains, even provided arms, to prevent locals or deserters from pilfering; and afterwards helped tend wounded and recovered equipment from the battlefield.

Soldiers were required to cook their own meals, but occasionally a camp follower was hired as a cook for officers, who often pooled their resources and ate together. It was regarded as one of the best jobs in camp because of what was overheard during meals. Not military secrets, but news from home. Companies were typically recruited from the same town, and regiments from the same region of a state. Because only about a third of Americans could read, soldiers who received letters often asked their officers to read those precious messages from home to them. Avoiding personal details, officers would share news from home around the dining table, and privileged cooks strained to overhear, later sharing news of home with other wives.

Much described here is also true of British camps. It was a time-honored and respected tradition for British wives to follow their soldier husbands, even across the ocean. Many unmarried women pursued relationships, even temporary dalliances, with British officers and soldiers. Unlike American soldiers, who were paid infrequently and then in devalued Continental script; British soldiers were paid regularly and in hard currency. The largess of the British army, and the availability of marriageable men with ready coin, resulted in persistent groups of camp-following wives, mistresses, and prostitutes.

Depending upon whom you consult, between 17% to 19% of Americans were “Loyalists” or “Tories.” The British military command in America formed “provincial” regiments or battalions of American Loyalists. Their wives faced the same choices, often in even more harsh manner since they were further in the minority and states sometimes condemned Loyalist property. Loyalist battalions had the highest percentage of camp followers who often lived in what were called “refugee” camps.

Camp-Following Heroines

Of course many are familiar with women like Martha Washington, Lucy Knox, and later Eliza Hamilton who followed their officer husbands to camp. But most camp followers are largely forgotten, only a few live on as heroines of the revolution. Probably the most famous we know by the nickname “Molly Pitcher.” Although that name is probably an amalgamation of several women’ s stories, one of them was Mary (Ludwig) Hayes.

Mary followed her husband, an artilleryman, to war. Her first camp was Valley Forge, where her husband was trained by Baron von Steuben in early 1778. She was a water carrier, and during training would bring water to the guns in a pitcher, not only for drinking, but for cleaning and cooling the gun. When in need, the men called out “Molly! Pitcher!”

In June 1778, as British forces withdrew from Philadelphia and marched across New Jersey to New York City, Washington’s army caught up with them at Monmouth. It was an excruciatingly hot day – more men fell from heat exhaustion than from wounds. During the battle, as Mary was bringing water to the gun crew, her husband was wounded while loading the cannon. Mary picked up his rammer and continued to clean and load the gun through the battle.

According to witnesses, at one point a cannonball passed between her legs, tearing away her petticoat, to which she reportedly remarked, “well, it’s a good thing it went no higher.” After the battle George Washington asked about the woman he’d seen manning the gun, and in honor of her courage issued Mary Hays a certificate as a non-commissioned officer, making her the first and only female NCO of the Continental Army.

Sarah Osborn was a camp follower who trekked from New York to the war-winning siege at Yorktown, Virginia. She is documented as carrying food and coffee to the troops in the trenches while under fire. When George Washington asked if she was afraid of the British cannonballs, Sarah replied “No, the bullets would not cheat the gallows… and it would not do for the men to fight and starve too.” Sarah lived to be over 100 years old, and is one of the few camp followers to have had her picture taken.

Margaret (Cochran) Corbin is another camp follower worthy of remembrance. Also from Pennsylvania, Corbin followed her artilleryman husband, John Corbin, to the army in 1775. Like Mary Hays, Margaret carried water to the men during the battle for Ft Washington, on Long Island in November 1776. Also like Mary Hayes, her husband was killed during the battle and Margaret assumed his role in manning the gun. During the battle she was wounded three times, to her left arm, chest and jaw. British doctors saved her life and later returned her to the Continental army.

She was sent to recover at a hospital near Philadelphia. In 1779, in recognition of her bravery, Congress granted her the first military pension awarded to a woman. Unable to use her left arm due to wounds sustained in service to her country, the army appointed her to the Invalid Regiment, made up of wounded troops who could no longer serve in the field. She remained in the army, stationed at West Point, for the rest of her life.

Afterwords

After the war ended, even years later, many officers wrote commentaries about camp-following wives. Most reflected on the value that camp-following wives brought to the army. They filled roles that were desperately needed, and in so doing released men to be soldiers. Contrary to Washington’s concern about distraction, women took over tedious camp chores thus enabling men to focus on training and their mission. Washington’s own remarks to Sarah Osborn and Mary Hayes show that despite his necessary limits on camp followers, he came to admire their courage, decency, and, above all, their contributions to liberty.

Women you may want to research: Anna Maria Lane and Deborah Sampson disguised themselves as men and served as soldiers during the revolution. Betsy Hager became a smith and repaired cannon and muskets. Polly Cooper, an Oneida woman, carried bushels of corn and supplies through the winter snows from the Mohawk Valley of New York to Valley Forge, helped nurse sick soldiers through the winter, and briefly became Washington’s cook.

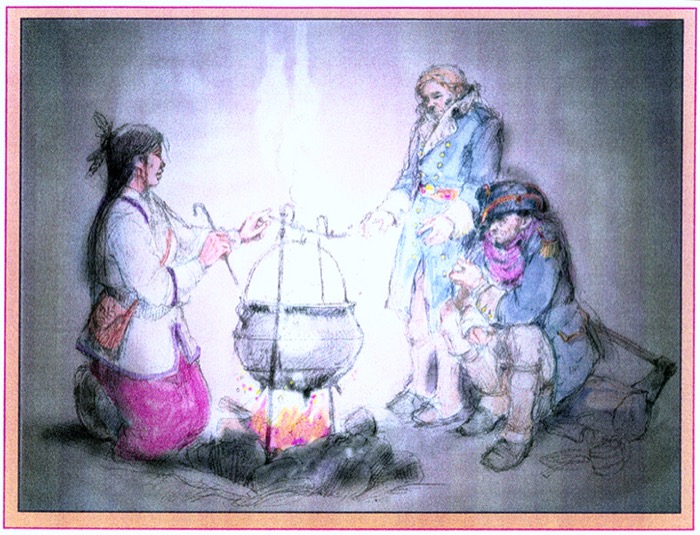

TOP PHOTO: British camp followers doing the laundry. (credit: Heinrich Schutz, Soldiers Cooking, April 1, 1798, from Revolutionary War Journal)