Summary: The Composition of the Declaration of Independence is a story of intrigue and pragmatism.

The Most Consequential Words in American History

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

This statement may be the most well-known sentence in the English language; what historian Joseph Ellis calls “the most potent and consequential words in American history.” We all know those words were written in June 1776, and adopted by Continental Congress as their “Declaration of Independence” on the 4th of July; a dramatic moment in the founding of the United States. We also have an impression of its drafting, as portrayed in the musical “1776”: Thomas Jefferson alone in his Philadelphia hotel room for days on end, surrounded by crumpled papers representing a multitude of false starts. But the truth… well, er… might be a little different…

On 15 May, 1776 Virginia declared independence from Britain and sent instructions to its delegates in Philadelphia to urge Continental Congress to declare independence for the united colonies. Virginian Richard Henry Lee did that on 7 June, rising from his green felt-dressed table on the floor of Independence Hall, to make a very carefully worded motion:

“That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.”

Lee’s motion kicked off a debate in Congress, one that required the delegates write home to each of their colonies to request instructions from their legislatures on whether to vote: “Aye” for independence, “Nay” to remain with Britain. Unlike today, where our smart-devices relay such requests at the speed of fiber-optic light, Continental Congress’ messages were written with quill pens, India ink and traveled at the speed of smell: the smell of horse.

A Revolutionary Assignment

Knowing it would take weeks for the legislatures to get the message, hold debate, and send instructions back to Philadelphia, under President John Hancock’s guidance Continental Congress organized three committees to begin the critical functions required by Lee’s motion. They established a committee to draft “Articles of Confederation,” which would be the constitution that the 13 united colonies would operate under after independence. Another committee was formed to draft proposals for treaties and alliances with foreign powers. And the third committee, considered the least important at the time, was formed to draft a press release; because if the colonies did declare their independence, they needed to explain it and provide justification; and the best way to tell the world would be to publish it in newspapers.

The “Press Release” committee, or what we now call the “Committee of Five,” included Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania), Roger Sherman (Connecticut), Robert Livingston (New York), John Adams (Massachusetts), and Thomas Jefferson (Virginia). According to John Adams, Jefferson received the most votes and became chairman. The “Five” began work on 11 June and it was, truly, a homework assignment. There was no private room available at Carpenter’s Hall, so they went to Jefferson’s room at Graff’s boarding house. Just exactly how much “work” is, well, debatable.

You see, all of “the Five” were members of at least three other Congressional committees, involved with oversight of finance, military, treaties, or espionage affairs, while also maintaining daily correspondence with their home constituencies and trying to keep in contact with families. There was a war going on and they were desperately busy men, clawing for time in their schedules. They weren’t interested in spending tons of that precious time writing a simple press release, and realized that it didn’t take five people to do that. So, they left Jefferson alone in his hotel room and got on with other pressing business, reconvening on evenings to provide input and edit Jefferson’s work.

For his part, Jefferson was pragmatic: less work, more better. For the three weeks prior to being put on Congress’ press release committee, Jefferson had been diligently working on another document for the same purpose. Remember that Virginia had declared its independence on May 15? Because of that, Virginia needed to develop a constitution and a plan of government. Jefferson, stuck in Philadelphia with Congress, had been insistently sending his own proposal to Virginia’s constitution committee in Williamsburg.

While the Virginian’s thought his ideas about government too radical, they did like the “preamble” to Jefferson’s document; which was an introductory explanation of why Virginia had decided to separate from Great Britain and an indictment of the British government in the form of a list of 22 grievances or justification statements.

Repurposed Declarations

By the time Congress appointed Jefferson to the Committee of Five, his work for Virginia was almost done. Since Jefferson had asked advice from others at Congress, John Adams in particular, the knowledge Jefferson was already working on a similar document may have influenced his appointment to the “Committee of Five” and selection as its chairman. They saw, as can we, that the introduction and list of grievances he’d written for Virginia met the needs for Congress’ press release announcing their declaration of independence. Not one to “reinvent the wheel,” Jefferson followed the practice of effective businessmen and lazy students, and reused his previous work; copying his justification of Virginia’s independence into his proposed press release justifying Congress independence.

Comparison of the drafts of Virginia’s 1776 Constitution and Jefferson’s drafts of the Declaration of independence (links at end) show almost two thirds of the Declaration was re-used from Jefferson’s Virginia constitution proposal. This similarity was noted in his lifetime, and when asked about it, Jefferson admitted that “both having the same object, of justifying our separation from Great Britain, they used necessarily the same materials of justification: hence their similitude” (Jefferson, April 1825).

Most of the Declaration’s final paragraph is Lee’s motion, exactly as Congress adopted it on 2 July, 1776. While other members of “the Five” added critical substance to Jefferson’s work (which Congress later edited substantially), about 85% of Jefferson’s final draft Declaration is re-used from other work. Meaning that Jefferson’s most arduous task, and the source of any crumpled papers strewn about his floor, was to introduce Congress’ declaration to the world and explain its rationale. He did it in three pithy sentences: “When in the course of human events…”

Conclusion

So, parents, when you catch your 8th grader reusing previous work for their current assignment, you might consider Jefferson’s homework pragmatism… but only if they tie the previous work to the current assignment with three pithy sentences that could stand the test of time as “the most potent and consequential words in American history.”

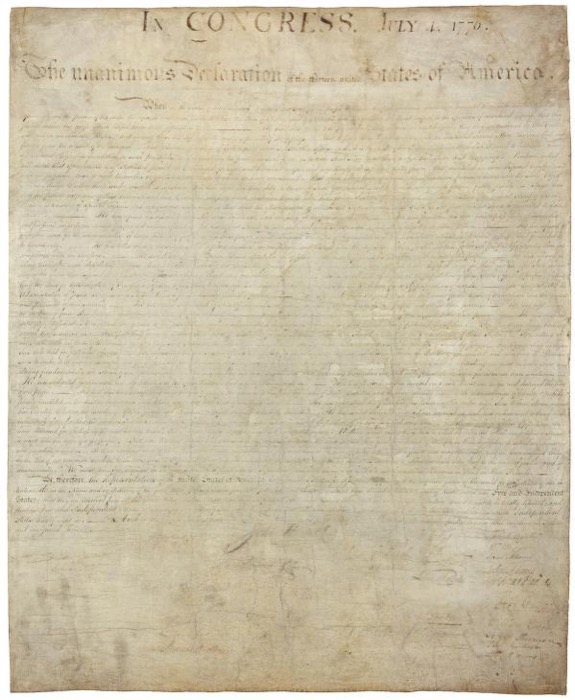

TOP PHOTO: Declaration of Independence (1819), by John Trumbull. (credit: John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons