The Portrait of George III

The State Portrait above depicts George William Frederick, Prince of Wales, just 22 years old, in his coronation robes about to become the next monarch of Great Britain. Alan Ramsay began the portrait in July of 1761 in anticipation of George III’s coronation later that year. We rarely talk about George III’s role in the American Revolution; or his responsibility for it. Nor do we acknowledge that while he was cast under bitter words of “tyrant” and “oppressor” in America, in Britain he was probably the most popular of the first five “Hanoverian” or “Georgian” monarchs.

George served a complex reign of almost 60 years, the first fifteen of which, when he was young, inexperienced and ill-advised, decided the fate of the American colonies. During the last twenty he was titular king but insane, and his son officially took over royal duties as Regent from 1810-1820.

Ramsay simultaneously painted nine virtually identical copies. It is an enormous painting, 9’ 8” tall by 6’ 3” wide, mounted in a lavish gilt frame. George was 5’ 11” tall in life, and in the portrait, from the heel of his right shoe to the top of his head, he is 5’ 11 ½”. He was painted life sized because the purpose of the portrait was to introduce him to his public.

One of these portraits was to hang in the monarch’s portrait gallery at the palace; the copies were to go on tour throughout his dominion: Britain, parts of France, some British colonies, and the principality of Hanover, in Germany, where George was also hereditary head of state, known as the “Elector.” In the 18th century, unless your first name was “Duke,” “Earl,” “Baron,” or “Viscount,” you were very unlikely to ever meet or even see your monarch in person. So instead, he came to your local cathedral, castle, or courthouse as a travelling portrait, where, as a good Briton, you would queue up to pay your shilling and meet your monarch… as Ramsay depicted him: glorious in his coronation gold silk damask and ermine.

That is, you were supposed to. This portrait never toured. George did not like it. First, the crown, which is not on his head so that you can appreciate his noble brow, is stuffed in a corner on a table behind George’s left hand. His “sinistrorse” hand. In Greek mythology (and everyone in the 18th Century adored the ancient Greeks) when Prometheus devised his evil plot to defy the gods and steal fire (representing knowledge and civilization) as a gift to humans, he was depicted handing fire over with his left hand, angering the gods and creating the first of the human tragedies. In the 18th century noble parents went to some lengths to avoid their children being left-handed; yet here was Ramsay’s portrait, implying George was pushing aside the crown with his left hand, surely a “sinister” sign of impending tragedy for George’s reign.

Second, George did not like his bearing depicted in the portrait. The crown is behind his sinister hand, and George is looking away from it in a melancholy expression, as if to say “I’d really rather be doing something else;” an inappropriate pose for a portrait whose purpose was to introduce a monarch to his subjects. George might have been peculiarly sensitive to this notion because it was true; at least a little… and probably much more.

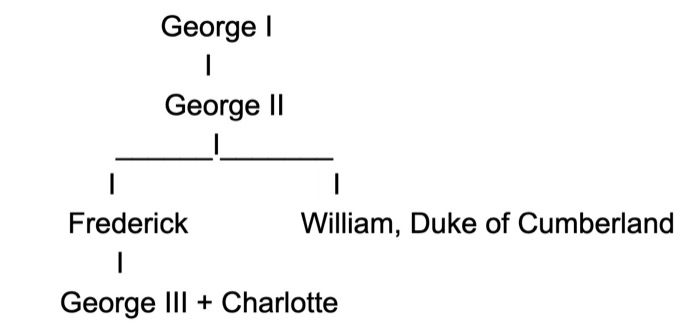

King George III’s Predecessors

George III’s great-grandfather, George I, did not get along with his eldest son, George II, for both political and personal reasons. The king went so far as to imprison George II’s children in the palace and banned George II and his wife from the grounds. George II repeated the mistake with his oldest son. To avoid palace imprisonment, Prince Frederick (George III’s father) was left to grow up in the care of his great uncle the Prince-Bishop of Osnabruck, in Germany. Freddy did not see his father or mother from the age of 7 to 21. Instead, he saw his grandfather for four months every summer when George I left Britain to rule in Hanover.

By the time his grandfather died and he was shipped to London, Freddy was a full supporter of his grandfather both emotionally and politically, in direct opposition to his father. When he married a short time later, to avoid his children being taken prisoner by his father the King, as had happened to his siblings, Crown Prince Frederick moved them from the palace into a country villa known as Richmond House. It was outside the city in a pastoral setting; and is primarily where his oldest son, who would become George III, grew up.

George III’s Early Years

Young George had been born prematurely, was not expected to survive infancy, and was slow to develop physically. He was well educated but shy and reserved. George III enjoyed the lifestyle, the ability to roam the countryside and talk with neighbors, and learned English from the locals at an early age. As opposed to his German parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, nanny, tutors, servants, staff, and even his future wife, George’s English was native-learned as a child and he spoke English as a Briton, even with a mild countryside delivery; which later in life endeared him to the public.

George became engrossed in the science of farming, which he championed throughout his life, and enjoyed astronomy. Since his father went into London to conduct political business at his official Leicester Square residence, young George III lived an idyllic life unencumbered by the duties and regal responsibilities of palace life – or by palace intrigue; of which there was plenty.

William, the Duke of Cumberland

George II’s emotionally and politically strained relationship with his heir, Frederick, the Prince of Wales, meant he doted instead on his second son, William, Duke of Cumberland (George III’s uncle). He elevated Cumberland rapidly and bestowed responsibilities that should have gone to his eldest son. Cumberland found an interest in military affairs and, after a brief stint in the navy, aided by his position as “spare to the heir,” quickly rose through army ranks. He took the field with his father and was wounded in the leg during the War of Jenkin’s Ear, an offshoot of the War of Austrian Succession, where George II became the last British monarch to lead troops on the field of battle.

King George II used Cumberland to deliver speeches on his behalf, and left Cumberland in charge of Britain when he spent summers abroad ruling in Hanover. Cumberland again took the field to personally take over command of the ill-equipped and ill-trained British Army after its initial failures during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. Though his defeat of “Bonny Prince Charlie’s” army at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 ended the rebellion, Cumberland’s orders to murder wounded soldiers, prisoners and Jacobite sympathizers earned him the lifelong nickname of “Butcher.” Cumberland’s star was rising meteorically when the unexpected happened. In March of 1751 Frederick, Prince of Wales and heir to George II’s crown, died suddenly of a “lung injury.”

Under the 1701 Act of Succession, Frederick’s oldest son, 12-year-old George III, became the titular heir to the throne. He donned Frederick’s title as Prince of Wales but few believed he would ever be monarch. A premature baby, slow to develop, George was estranged from the palace and son to a man who was a political enemy to, and all but publicly disavowed by, the current King. Many Britons believed that George II’s second son, Cumberland, the rising military star, was the true heir to the throne.

With Frederick’s death Parliament passed a “Regency Act” making George III’s mother, Princess Augusta, the official “Regent” of her son, the new Crown Prince. But she was to be shepherded by a Regency Council, appointed and chaired by Cumberland. The King and Cumberland repeated ever-more-strongly-worded “suggestions” that the Crown Prince should move back to the palace, within the bosom of the royal family. Parliament checked Cumberland’s power to order the move, the King would not issue an edict, so Augusta steadfastly refused. She distrusted her estranged father-in-law, perceiving Cumberland as a threat to her son. She knew stories of young princes murdered within the palace walls, and was all too aware that George I had imprisoned George II’s children in the palace and then banished their parents. In Augusta’s mind, the only thing between Cumberland and the throne was the life of her son.

When the Seven Years War broke out Cumberland was named Commander in Chief of all British military forces. Although the numeric underdog, Cumberland’s experience as a military organizer paid off, and Britain began a series of victories that would eventually win the war. Cumberland looked to be securing the strings of power until he made a critical error. Cumberland argued to be made the field commander of George II’s Hanover Army. The army was small, untrained, and outnumbered three to one by French Forces.

Cumberland recognized the drain on British military required to bolster Hanover, and he decided to make a separate, private peace between Hanover and France. But his 1757 Treaty of Klosterzeven was terrible, he had no bargaining power and allowed for the Hanover forces to be disarmed and for France to occupy Hanover. It was nearly an unconditional surrender. George II was enraged, negated the treaty, ordered Cumberland back to London in disgrace, and relieved him of all military responsibilities. Cumberland retired to mistresses and horse races. His wounded leg never healed, and he slowly became grossly obese.

Thus, when George II died less than three years later in October 1760, his 22-year-old grandson was a titular heir with no experience, no pedigree and no wife.

The Reign of George III

The royalists took their time naming him to the throne and delayed his coronation for almost a year. His mother resolved the delay by arranging his marriage to 17-year-old Princess Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (a German duchy). She arrived in London on 8 September, and the marriage took place that afternoon at Chapel Royal, St James Palace. At the time of their marriage Charlotte spoke no English, but learned quickly (contrary to television portrayals, she spoke with a heavy German accent her entire life). The couple met at the chapel gate, but did not see each other until George lifted her veil at the altar.

…and that explains the look on George’s face in Ramsay’s portrait. All of this had to be floating through George’s mind as he stood for hours while Ramsay captured his features. The melancholy look was real: this should be his father standing here; George should not have been monarch until he was in his forties or fifties. He was about to assume a role for which he was completely untrained. Because of the estrangement from his Grandfather, George had never gotten those critical courses: How to play nice with Parliament 101, how to work with the Privy Council, 202, or how to work with the Archbishop of Canterbury, 303; because, remember, he was not just the monarch but also head of the Anglican Church. Within a couple months he would marry a girl he had never met. He would live in rarely visited palaces.

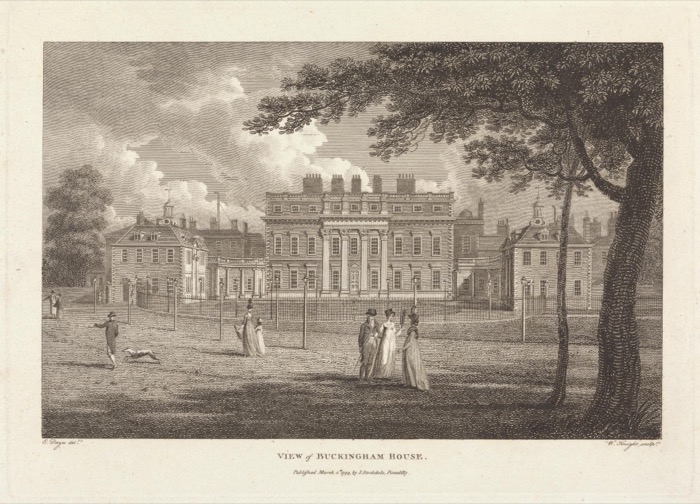

To accommodate his growing family, George III bought a “country estate” from the Duke of Buckingham as a safe haven for his wife, Queen Charlotte, in 1761. The manor was not far from St James Palace, the official royal residence. George gave his family the same gift that his father had provided him: the opportunity to live, grow, and learn outside of the pressures, and restrictions, of formal palace life. George added on to the estate as his family grew: he and Charlotte had 15 children, 13 of whom reached adulthood. Today George’s getaway home, greatly expanded and “palace-ified” by succeeding monarchs, is known as Buckingham Palace.

George’s inexperience plagued his early reign. He failed to form a political agenda, or even an advocacy. He was induced to issue the Proclamation Line in 1763, which alienated Americans who fought for Britain in The French and Indian war in exchange for bounty land issued by Britain on the “wrong side” of the line and angered colonists who had already settled to the west or viewed westward expansion as key to their livelihood. In the first 15 years of his reign, Parliament passed roughly 35 acts which placed tariffs and regulation on colonial imports and exports, taxes on everyday goods, limitations on currency in the colonies, or adjusted colonial borders; which impacted the economy and lifestyle of colonial Americans. Although able to wield royal veto over laws passed regulating the colonies, George never used it for Parliamentary laws, but did veto dozens of acts passed by colonial legislatures.

Conclusion

George gave the painting to his mother, who hung it in Carlton House, her private residence. During her reign, Queen Victoria had it installed as George III’s official state portrait. The copies were sold into private hands. At least seven are accounted for today, including an original completed in 1762 on display at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown, Virginia.

TOP PHOTO: George III Coronation Portrait, 1761, By Allan Ramsay – Royal Collection. (William Knight Keeling, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)