Summary: Benedict Arnold is one of America’s most notorious traitors. But was this Revolutionary War villain really just a victim?

Benedict Arnold’s Travel Claim: Justification for Treason?

The American Revolution introduced us to many men who remain our heroes. We immediately recognize Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Franklin, even without first names. But we also remember the anti-heroes, villains whose names remind us that freedom is precious, and that liberty can be lost from within. Chief among those is Benedict Arnold, whose betrayal of the American cause in exchange for the promise of £20,000 and a Major Generals commission in the British Army remains one of the most heinous acts of treason in history. Today the name “Benedict Arnold” is a synonym for “traitor.”

Arnold “turning coat” from successful American General to traitor still fascinates us, and there are many excellent books about Arnold. It’s natural to want to see the best in a person and many recent works equivocate Arnold’s treason, suggesting he’s unfairly treated. A key argument toward vindicating Arnold is that Continental Congress mishandled Arnold’s expenses in Canada, delaying restitution and short-changing him, justifying his treason. But, the record of Congress’ reimbursement, contained in our public records, show Arnold delayed filing his claim; and reveal Congress generously overlooked his own responsibility for a major loss.

Arnold’s Quebec Campaign

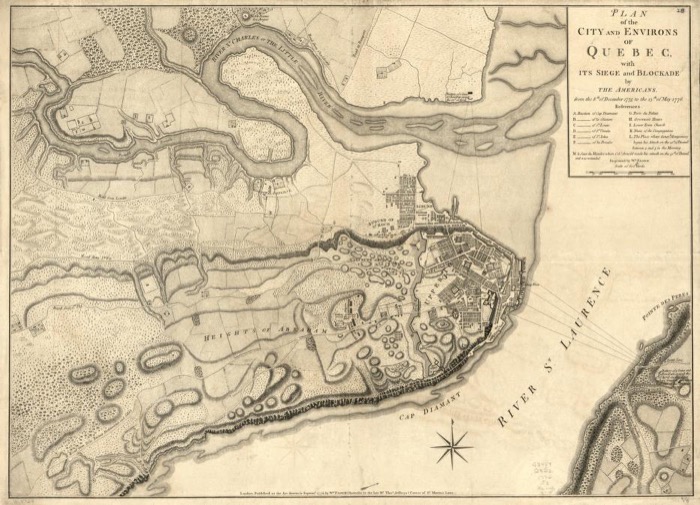

In 1775 the American military invaded Canada to prevent the British military from using it as a staging ground and breadbasket for conducting war on the rebellious 13 colonies. The primary attack was launched in early August from Ft Ticonderoga towards Montreal by a small army commanded by General Richard Montgomery. As an afterthought, to complicate British defense of Canada, a second attack was planned to attack Quebec City. Benedict Arnold lobbied heavily to lead this expedition, and George Washington granted Arnold’s command.

Arnold was up against myriad unknowns. Maps of the Maine wilderness and eastern Canada below the St Lawrence were few and inaccurate. It was true wilderness, no established trails. Arnold thought the distance was 180 miles; his chosen route was really about 280. He carried 20 days’ supply of food; the march took 45 days. He departed Ft Western, modern day Augusta, Maine, on 25 September with 1,116 men.

The leaves were already turning; winter on the way as they started up the Kennebec River. Arnold hired guides who’d never made the trip. The route hoped to take advantage of known waterways, but the boatbuilder skimped on materials, using green wood that soon shrank and the boats leaked. The men had to slog through half frozen bogs, retrace their steps when routes proved impassable, and portage equipment, ammunition, provisions and boats at carrying places between rivers and ponds, as well as up and over the Appalachian Mountains. Less than halfway to Quebec, Colonel Roger Enos grew wary of Arnold’s leadership and failure to properly provision the army, and turned back towards Ft Western with about 400 men and half the remaining provisions. Those who continued the march found starvation their greatest enemy: men resorted to boiling leather portions of their equipment and clothing and even ate one officer’s Newfoundland dog; some died of starvation and exposure.

On November 8th, when Arnold’s 600 bedraggled men finally emerged from the wilderness onto the St Lawrence River, just upstream from Quebec City, they found Arnold’s trading ship, the “Peggy”, awaiting them. A commercial trading ship before the war, Peggy carried trade goods from ports in the Caribbean to Arnold’s apothecary in New Haven, Connecticut. How nice to think Arnold had arranged for a cargo of food, clothing, and blankets to have met his “famine-proof” troops at the far end of their exhaustive trek. But no, Peggy carried a commercial cargo for sale in Canada: rum and 25 horses with their fodder. Arnold should have offloaded Peggy’s cargo and sent her back to Connecticut: winter was fast approaching, and the St Lawrence froze solid in winter. Nobody left wooden ships in the St Lawrence during winter. Upstream, near Montreal, the Americans had captured the ship “Gaspe,” which they carefully sank so she wouldn’t be crushed by ice, then raised her the following spring. Once it became obvious Peggy would not survive the ice, Arnold had soldiers haul her onto the rocky shore of Isle Orleans. In mid-winter Arnold had soldiers offload her cargo and sold the rum to his own army. By spring, after drying out and being grounded on the rocky shore, her seams were sprung; Peggy wasn’t seaworthy.

The Americans hadn’t been able to take Quebec nor control the St Lawrence River, and were withdrawing from Canada ahead of British reinforcements. With the British controlling the lower St Lawrence, and over 100 cannons mounted on Quebec’s fortress walls, including massive 32- and 42-pound guns that commanded the river shore to shore, Peggy was going to be lost to Arnold. Even if she could have been repaired, she would have been captured if she tried to escape to the sea.

In searching for a way to turn lemons into lemonade, Arnold had Peggy turned into a fire ship. On the evening of 3 May, 1776, Peggy’s sails were set, her wheel lashed, the fuse to the combustibles on board lit, and she was shoved off towards Quebec a couple miles away in the faint hope she would somehow make it past Quebec’s formidable artillery and set fire to some of the few British ships moored below the city. It was a gesture of utter futility. Peggy was unmanned; with no one at the pumps she was already sinking. She would have needed to make a precise left turn across the current to approach the few ships moored near the city, and there was no one on board to turn the wheel, let alone the sailors needed to tack her sails. Quebec’s gunners blew her to pieces hundreds of yards from the harbor. By June the American army, suffering from smallpox, wounds, and desertion retreated towards New York. The invasion of Canada had failed.

Arnold’s Expenses in Canada

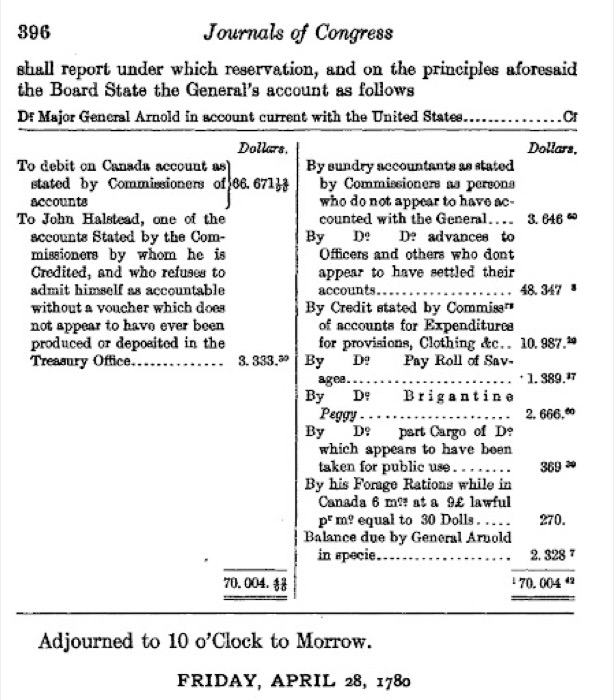

Arnold let his travel voucher languish – somewhat understandable for a busy man. He first submitted his claim to the Continental Army Paymaster in early 1779, almost three years after the withdrawal from Canada. Arnold’s own surviving ledgers show he was advanced £10,405 in “specie” – gold and silver coin – which was about $35,000 Continental dollars. He also received paper money and made other contracts with suppliers on Congress’ behalf. In all, he was accountable for $70,004, the modern equivalent of about $695,000, which the Army Paymaster could not reimburse. The Army deferred his claim to Congress, which Arnold delivered on 27 April, 1779. Arnold figured that Congress owed him a bit more than $2,500. A week later, Arnold began his treasonous correspondence with the British.

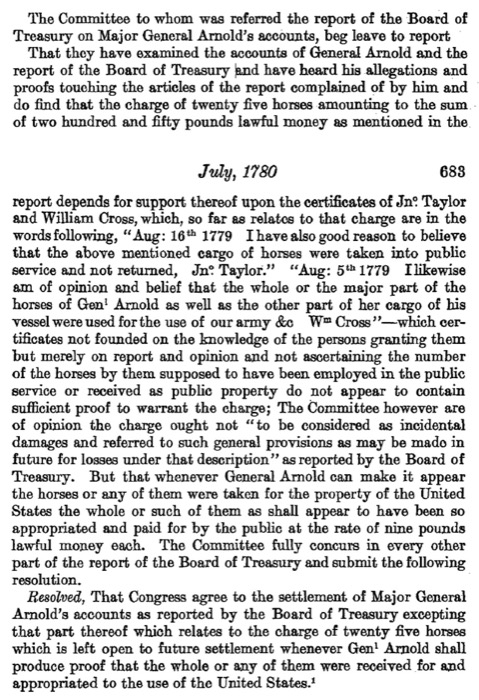

Arnold couldn’t produce receipts for all the money he’d spent in Canada, some due to his own bookkeeping, and claimed other receipts were lost during the retreat from Canada. But these were not the crux of the problem; Congress eventually accepted all of Arnold’s expenses except a disagreement with Canadian supplier John Halstead, who claimed Arnold never paid him roughly £1,000 (equal to $3,333.30). The real problem was Arnold’s private losses: his voucher demanded reimbursement for the loss of Peggy ($2,666) and her cargo of horses and fodder ($972.32).

Congress established a committee to adjudicate Arnold’s claim. The committee believed Arnold sending Peggy to Canada was a commercial venture of his own risk, not theirs, and did not accept that Peggy was consumed as a “military necessity.” But they told Arnold that if he could get two officers to sign affidavits that the 25 horses were used for a military purpose, they would reimburse their cost; but at the going rate for horses (£8) as opposed to the inflated amount he claimed (£10). Arnold and the committee engaged in a lengthy dispute, with Arnold insisting Peggy’s demise as a fire ship was militarily necessary. Congress grew weary of Arnold’s insistence, and of him publicly bad-mouthing Congress over the claim.

At the same time, Arnold was being court-martialed for charges stemming from selling confiscated goods to British officers and delivering them from Philadelphia to New York using Continental Army wagons; and the claim sat idle for four months. By early 1780 Arnold was convicted on two minor charges and was reprimanded by General Washington, and in April Arnold resigned his post as Governor General of Philadelphia.

Unknown to Congress, Arnold had already begun liquidating his assets in preparation for turning traitor. He wrote Congress that even though he was owed $2,500, he would accept $2,000 in specie. In hopes of closing the Arnold problem, on 28 April the committee recommended Congress to pay all of Arnold’s claims. Congress did not agree. Although there was a flimsy excuse for Peggy, there was insufficient evidence of Arnold’s horses being used by the army. In compromise, on July 30 Congress allowed a balance due to Arnold of $2,328.70 in specie. They denied Arnold’s $972 claim for horses but provided the claim would be paid later if Arnold could demonstrate any of his horses “were received and appropriated to the use of the United States.” Arnold never made the claim, instead defecting to the British in September 1780.

Conclusion

You decide. Who was responsible for the delay in Arnold’s claim? Did Congress dither in resolving it? Since Arnold began his defection to the British eight days after he filed the claim with Congress; was any delay by Congress a legitimate excuse for treason? Did Congress short-change Arnold, or was America gypped when Congress paid for the loss of Arnold’s private trading ship?

TOP PHOTO: Colonel Benedict Arnold who commanded the Provincial Troops sent against Quebec, through the wilderness of Canada and was wounded in that city, under General Montgomery. London. Published as the Act directs 26 March 1776 by Thomas Hart. (From the Anne S. K. Brown Collection at Brown University, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)