Summary: Discover the context of the tea party protests in America that helped lead to the Revolutionary War.

Tea Party Protests Across the Colonies

While modernly the goblins and ghouls of All Hallows Eve have just emerged from sugar highs, the turkey nears the table, and vendors have already shifted our gaze towards the commercial frenzy that should be remembered as the Nativity, 251 years ago it was Tea Party time.

In October of 1773, the British East India Company sent seven ships to America containing about 600,000 pounds of tea. Four to Boston, and one each to Charleston, Philadelphia and New York. Arriving at different times from December into January, each was met by rejection by hostile Americans angered that Parliament was manipulating law to bail out a private company. Because of that, the “Boston Tea Party” wasn’t the first Tea Act protest in America, nor even the first in Massachusetts.

From December 1773 through the end of 1774 there were at least 15 tea protests in the twelve original American colonies. At that time Delaware was still the “Lower Three Counties of Pennsylvania On the Delaware,” that had some independent legislation, but shared the same Governor with Pennsylvania. Delaware did not declare its independence from Pennsylvania until 20 June, 1776. The tea protests would become part of the lead-up to the signing of the Declaration and the Revolutionary War.

Fun Tea Facts

Tea tariffs were Britain’s largest single revenue source.

Parliament’s “Navigation Acts” required that all tea be imported first to Britain before being re-exported to colonial ports, and there was a massive tariff on tea imported into Britain; up to 110% of its retail value. Between 1760 and 1810 tea import taxes raised £77 million. Additionally, in 1767 Parliament’s Townsend Acts taxed 91 articles exported from Britain to the American colonies, including an additional three pence per pound (about 10%) tax on tea exported to the American colonies.

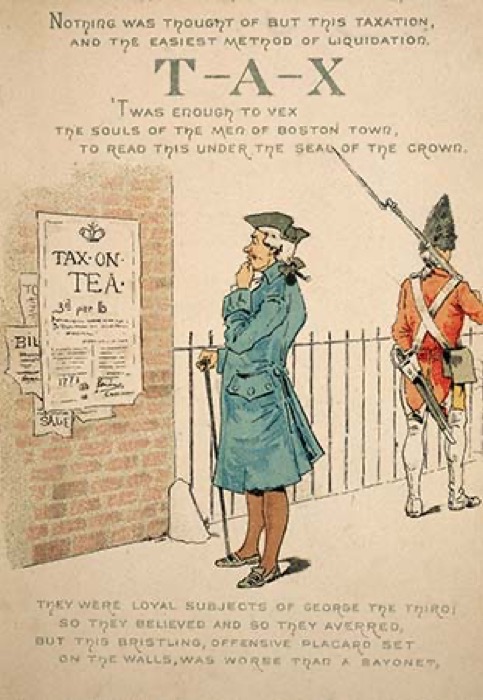

Americans protesting “taxation without representation” boycotted British goods. Britain sent thousands of troops to enforce them, resulting in riots – including the “Boston Massacre.” Realizing that the Townsend Acts were responsible for huge expenditures as well as a loss of tax revenue from America, Parliament repealed the Townsend Acts in 1770 except for the tax on tea. It then issued the “Declaratory Act” which stated their inherent right to place taxes on American Colonies; and the tax on tea became symbolic of “taxation without representation.”

The Tea Act was passed to save the British East India Company, the “EIC” from financial failure.

The EIC was the largest private stock company ever created, controlling over half of the British Empire’s trade. But it was losing money hand-over-fist primarily as a result of gross inefficiency and bad management. Because of its position in world trade, producing tax revenues which primarily funded the British treasury, it was considered “too big to fail.” In 1772 Parliament had “bailed out” the EIC with a loan of £1.5 million; the modern equivalent of about (depending on currency valuations over time) $1.5 billion. It remains the largest government bailout of a privately held company in world history.

The EIC had nearly 18 million pounds of tea slowly rotting in British warehouses.

The EIC failed to adapt to changes in consumer habits. Naval conflicts and trade blockades during the “Seven Years War” from 1755 to 1763 (and yes, that’s actually eight years) created tea shortages throughout the British Empire. Consumers shifted to drinking Dutch tea, which came from the very same growers in China as EIC tea and, despite British propaganda, tasted the same. Although illegal, Dutch tea was routinely smuggled throughout the British Empire. Once British consumers realized there was no real difference in quality, they were hooked by the much lower cost of Dutch tea. This trend was exacerbated in America by the general boycott of British goods as a protest to the Townsend Act tariffs passed in 1767.

In 1772 Dutch Bohea (pronounced “bO-hee”), the cheapest and most prevalent variety of tea, sold for 2 shillings and 1 penny per pound (25 pence, about $41 today). EIC Bohea, because of the massive import tariff in Britain, sold for 3 shillings per pound, and American consumers had to pay the additional Townsend tea tax of 3 pence per pound (total 39 pence, about $65 today). British consumers, particularly in the American colonies, shifted to drinking Dutch tea or alternatives such as chocolate or coffee, a staple in America since its original colonization, which were untaxed and just over half the cost of EIC tea. Despite the dramatic decrease in tea sales, between 1765 and 1773 the EIC, desperate to control the global tea trade and to drive the Dutch out of business, consistently increased its import of tea into Britain, resulting in the massive surplus.

The Tea Act cut taxes, but only for the EIC.

Prior to the Tea Act, tea was sold throughout the British Empire through a series of independent vendors called “consigners” who were licensed by the government to bid on lots of East India tea. The EIC would then ship the tea to the winning consigners who were the point-of-sale retail vendors to the public. The Tea Act changed this system. The EIC was allowed to license their own consignors, which cut out the middleman. Additionally, for every pound of tea sent to the EIC’s American consignors, Parliament rebated the 110% tea import tariff to the EIC. Even including the 3 pence per pound Townsend tariff, this enabled EIC consignors to sell EIC supplied Bohea tea in the colonies for 2 Shillings per pound, underpricing Dutch tea by a penny per pound.

But the Tea Act cut out all former merchants who operated under the consignor system. They didn’t get the rebate on the import tax, and the EIC limited the number of consignors. Throughout the empire former tea merchants were cut off from the tea trade, ruining many and generating widespread opposition to the Tea Act. The tea act was also temporary, it only applied until the EIC reduced their surplus to 10 million pounds of tea. Parliament intended, and Americans realized, that by the time that happened smugglers would be out of business and exorbitant taxes would return with no recourse to Dutch tea

Governor Hutchinson forced the Boston Tea Party.

Massachusetts Governor Hutchinson had been a tea consignee for years. According to his letters, he annually profited between £1,000 and £1,500 from his tea sales. As an established consignee he wasn’t eligible for an EIC license, so he arranged instead for friends and relatives to get EIC licenses. There were six EIC consignees in Massachusetts: two were Hutchinson’s sons, two were in-laws, and two were close friends. Hutchinson was cornering the tea market. Under the terms of British customs clearance rules, the tea ships arriving in Boston had to be unloaded and the duty paid within 20 days of arrival in port; if not, the ships and their cargo became the property of the royal governor. In Boston, that was Hutchinson.

All of the ships carrying tea to Boston were owned by Boston or Nantucket men. One ship, the William, went aground on Cape Cod trying to enter the harbor in a storm. Two were whalers which had delivered spermaceti whale oil to Britain and took the cargoes of EIC tea so they did not have to travel home empty. The owners repeatedly petitioned Hutchinson to allow the ships to return to Britain with the tea, but Hutchinson ordered the British harbor guns to fire if the ships tried to leave. The Dartmouth had been first to arrive on 28 November, meaning that December 16th was the 20th day. That day Dartmouth’s owner, Francis Rotch, tried to reason with Hutchinson, who would not budge. When Rotch returned without a solution, the Sons of Liberty unloaded the tea from all three remaining into the harbor, defeating the seizure clause.

Coffee has always been a staple drink in America.

Before coming to the first permanent English settlement of Jamestown in 1607, John Smith, the very same person who was saved from death by, but did not marry, Princess Matoaka (Pocahontas), visited Turkey where he was introduced to coffee. Smith brought coffee-making apparatus to America; coffee beans appear in letters from Jamestown and in resupply goods. Similarly, a mortar and pestle-style coffee grinder was brought to America aboard the Mayflower. Although tea was the prevalent luxury drink, the American boycotts of British goods and the cost of tea driven by British tariffs cemented our national preference for coffee.

Tea Act protests were not called “Parties.”

That moniker didn’t attach until much later. The first use of the term occurred about 1836, when a newspaper wag described the group of men who dumped the tea in Boston as a “party of patriots disguised as redskinned Indians.” Initially the protests were labeled by what happened, such as the “destruction of the tea,” “refusal of the tea,” “dumping of the tea,” “burning of the tea” or “seizure of the tea.” In the 1870’s, after British “High Tea” services became popular during the Victorian era, Americans poked fun at British “Tea Parties” by reminding them that we preferred ours salty, and the “Tea Party” moniker has stuck ever since.

All the tea in China.

At the time of the tea parties, most tea was coming from China, with just a bit from Japan and “Java” (Indonesia). It wasn’t until 1778 that native tea plants would be discovered in the Assam region of India. The EIC was responsible for initiating cultivation of tea in India and Sri Lanka.

The “Redskin” controversy.

A popular 1773 Boston newspaper account attributed the “dumping of the tea” to “fifty and some odd red skin-painted Mohawk Indians,” a phrase later re-used by other writers reminiscing about the event. Of course, it was really Boston’s Sons of Liberty. In 1773 America was typically depicted in political cartoons as a female Native American, and the disguise signified that the protesters identified as Americans, rather than colonial British subjects.

In 1927 a football team was created in Boston, named the “Boston Braves.” Upon purchasing the team in 1932, George Marshall changed the name of the team to differentiate it from the Boston Braves baseball franchise. He chose “Redskins” in honor of the “fifty and some odd” tea-dumpers. The team moved to Washington in 1937, and the name became controversial as a crude epithet once the connection to Boston and the Tea Party was forgotten. In 2020 pressure from several NFL Team owners and sponsors resulted in retirement of the name.

| Tea Act Events in the American Colonies | ||

| Date | Location | What Happened? |

| 9 Dec 1773 | Charleston, SC | The ship London arrived with about 250 crates of tea. Unloaded onto the wharf, it was unclaimed as all of the South Carolina tea consignees had resigned. On the 20th day the tea was seized by customs officials and locked into the Exchange Building, no tax paid. Sold in 1776 to finance the revolution |

| 11 Dec 1773 | Boston, MA | The ship William, carrying 56 crates of tea and 300 street lamps, ran aground 11 December near Provincetown while trying to enter Boston harbor. All of the streetlamps were recovered, and within months provided Boston’s first street illumination. 53 chests of tea were salvaged intact and secretly taken by Governor Hutchinson to Boston. Hutchinson stored them at Castle William, a fortress on one of Boston harbor’s islands, and then later, having paid nothing for it, privately sold the tea at a massive profit. |

| 13 Dec 1773 | Lexington MA | Citizens voluntarily consign all tea in the homes to a bonfire in protest of the Tea Act |

| 15 Dec 1773 | New York, NY | 200 merchants, lawyers, artisans, and businessmen sign a petition proclaiming the Tea Act:”… involves our slavery, and would sap the foundation of our freedom, whereby we should become slaves to our brethren…born to no greater stock of freedom than the Americans-the merchants and inhabitants of this city, in conjunction with the merchants and inhabitants of the ancient American colonies, entered into an agreement to decline a part of their commerce with Great Britain, until the above-mentioned Act should be totally repealed.”In support, 3,000 new Yorkers protest against the Tea Act at City Hall. |

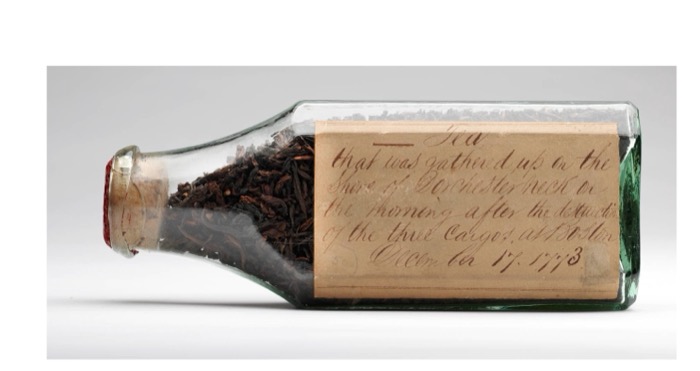

| 16 December 1773 | Boston, MA | On the 20th day after the whaler Dartmouth arrives with tea aboard, to prevent the ship and cargo from being seized under the customs laws, the Sons of Liberty board three ships at Griffin’s wharf and dump 342 chests of tea into the harbor (two chests were private cargo) |

| 25 December 1773 | Philadelphia, PA | The ship Polly, with 697 chests of EIC tea aboard, arrived in Chester, PA. Several Philadelphians greeted Capt Ayres and “escorted” him to Philadelphia. Ayres is presented a broadside by an angry crowd of 8,000, after which he returned the tea to Britain: You are sent out on a diabolical Service; and if you are so foolish and obstinate as to complete your Voyage, by bringing your Ship to Anchor in this Port, you may run such a Gauntlet as will induce you, in your last Moments, most heartily to curse those who have made you the Dupe of their Avarice and Ambition.What think you, Captain, of a Halter around your Neck—ten Gallons of liquid Tar decanted on your Pate—with the Feathers of a dozen wild Geese laid over that to enliven your Appearance?Only think seriously of this—and fly to the Place from whence you came—fly without Hesitation—without the Formality of a Protest—and above all, Captain Ayres, let us advise you to fly without the wild Geese Feathers. |

| 3 Jan 1774 | Princeton, NJ | After hearing about the Boston Tea Party students seize about 12 pounds of tea from college stores and “known tea drinkers” and burn it in a bonfire in front of Nassau Hall |

| 25 Mar 1774 | Wilmington, NC | Local women protest by burning a small amount of tea |

| 18 Apr 1774 | New York Harbor | Captain Lockyear of the Nancy, was informed that New York would not allow his cargo of 698 crates of tea to be landed, and that the EIC consignee refused to accept it and advised it be returned to London. Threatened with tar and feathers, Lockyear resupplied and returned to Britain with the tea. |

| 22 Apr 1774 | New York Harbor | Failing to learn his lesson in Charleston, the Captain of the ship London attempted to quietly smuggle a small cargo of tea to New York for his own profit. 18 crates of tea dumped into the Hudson River. |

| 19 Jul 1774 | Charleston, SC | Captain Maitland of the Magna Carta offered to defuse an angry mob by voluntarily throwing his cargo of three crates of tea into the harbor, but then went to the Customs House to pay the duty to land it. Customs officials refused to accept the money because the tea had not yet been landed. When word leaked to the mob they boarded the Magna Carta to find one full chest and two quarter chests of tea aboard. Upon seeing the mob approach, Maitland fled to the Britannia, moored nearby. The mob took Maitland’s tea to the Exchange Building where it was stored with London’s cargo, and later sold to finance the revolution. |

| 1 Aug 1774 | Richmond, VA | The Virginia Convention adopts a boycott on import and sale of British goods “until such time as our grievances with Parliament are resolved.” |

| 15 Sep 1774 | York, MA (Maine) | 150 pounds owned by the ships owner and local Tory Jonathon Sayward was offloaded and impounded. Locals disguised as “Pickwacket Indians” broke in and stole it, but two days later it was returned to Sayward. Because it had been “stolen,” no custom duties were required, so no tax was paid, and Sayward kept the tea |

| 19 Oct 1774 | Annapolis MD | The Peggy Stewart arrives in Annapolis with a cargo of linen and 53 indentured servants. Enroute from England, the passengers told the Captain they found 17 packages, 2,320 pounds, of tea disguised as linen. The Captain informed the Maryland owner that a competing business owner in Britain smuggled tea in the cargo. To avert the wrath of the locals, the Maryland owner made a deal with the Sons of Liberty that allowed the linen and servants to be unloaded and Peggy Stewart then taken out into the harbor where it was burned with full sails and flags flying, with the tea still aboard |

| 25 Oct 1774 | Edenton, NC | 51 ladies form the Edenton Patriotic Guild and sign a resolution supporting North Carolina’s resolutions condemning the Tea Act and Coercive Acts |

| 27 Oct 1774 | Philadelphia PA | Continental Congress adopts the Virginia Boycott as a Continental ban on import and sale of British goods with immediate effect relative to the article of tea |

| 1 Nov 1774 | Charleston, SC | The Britannia, the ship which provided shelter for Captain Maitland of the Magna Carta four months previously, returns to Charleston with 7 crates of tea on board. The Charleston mob seized the tea and forced the importers to dump it into the harbor, with three hearty cheers after each. |

| 7 Nov 1774 | Yorktown, VA | In specific support of the Virginia and Continental Congress boycotts, Thomas Nelson, Jr. leads a committee aboard the ship Virginia riding at anchor and empties two half-chests of tea into the York River |

| 22 Dec 1774 | Greenwich, NJ | “The Last Tea Party”: forty patriots dressed as Native Americans seize and burn a small cargo of tea unloaded from the Greyhound. |

Conclusion

Some of the tea protests in America were small, some quiet, none were called “Tea Parties” at the time, and most are forgotten today. As we wrap up a year celebrating the revolutionary tea events that led us towards independence, it’s a good time to remember.

TOP PHOTO: The Author “dumping the tea” for the 249th anniversary of the Yorktown Tea Party (authors collection)

(The author is a founding member of America’s 250th Tea Party Committee)