Summary: During the period of the Revolution, slavery was much closer to being banned in America than most people realize.

Slavery Through the Eyes of the Colonists

One of the most difficult discussions for America’s “Founding Fathers” was chattel slavery. It remains one of the toughest topics we must face modernly. As we look back on the heinous institution of slavery with modern eyes, it’s difficult to understand how it was ever tolerated, let alone how it endured for so long.

But when we look back, we have the benefit of knowing the full story… of both America and of slavery: how it descended into an ever-darker institution, the blood that was spilled to end it, and the failure to defend against the resurgence of hate in the form of “Jim Crow” legalized racism. It’s hard to see the issue through the eyes of those who lived in British Colonies; whose frustration with the British colonial system led first to demands to uphold their rights as British subjects, and then an aspiration for independence.

Even after the shooting had stopped, the success of the American nation was uncertain, forcing representatives in Continental Congress, and later the Constitutional Convention, to reach compromise to foster the cohesion of the fledgling nation ahead of its basic premise of extending unalienable rights to all of our people. They did not know the price: that “four score and seven years” later slavery would lead to near destruction of the nation in a vicious Civil War; or that 250 years later we would still be struggling to heal.

The crucial topic of slavery is just one of the important issues dealt with in the new film The American Miracle: Our Nation Is No Accident. This stirring docudrama will be released in theaters nationwide for three nights only on June 9, 10, and 11. It delves into the untold story of America’s founding, including the remarkable string of unlikely escapes, providential battlefield victories, and the bruising battles of the constitutional convention that formed the basis for the new country. Tickets are on sale now; space is limited.

Condemning Slavery in the Declaration of Independence

The draft proposal for the Declaration of Independence which Jefferson delivered to Continental Congress contained a paragraph criticizing the institution of slavery and condemning the British for imposing it on America. Remember that this draft was a product of the “Committee of Five,” meaning that Ben Franklin, John Adams, Robert Livingston and Roger Sherman contributed, reviewed and approved the inclusion of this paragraph. The Declaration asserted that King George:

…has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce… (emphasis in the original, see Jefferson’s original Rough draught)

Jefferson’s assertion that the Monarch, and Parliament, had endorsed the British slave trade was well known then and now. The British government openly supported slave trafficking and considered it essential to the East India Company’s profit margin. Most Parliamentary ministers – and King George himself – owned stock in the British East India Company (the “EIC,” or “The Company”). But, Jefferson’s statement that King George had vetoed laws (“prostrated his negative”) that American colonies passed to limit slave trade is new information for most modern Americans.

What was Jefferson talking about?

Attempts to Curtail Slavery Through Taxation

Before the revolutionary war, the colonial legislatures of eight American colonies adopted, or attempted to adopt, measures which either taxed or punished importation of slaves:

PENNSYLVANIA: never popular in Pennsylvania, slavery reached its peak about 1750, when there were about 6,000 slaves of the total population of around 120,000 (5%, including the counties which later became Delaware). Quaker society discouraged slave ownership and often cast out members who did not free their slaves. On 27 Nov. 1700 the Pennsylvania Assembly installed a 20-shilling levy on slave imports, doubled it to 40 shillings in 1706, and in 1712 adopted an additional £20 pound import tax on slaves. In 1731 King George II ordered Pennsylvania’s governor to vacate the tax and to prohibit any colonial law imposing import duties on slaves.

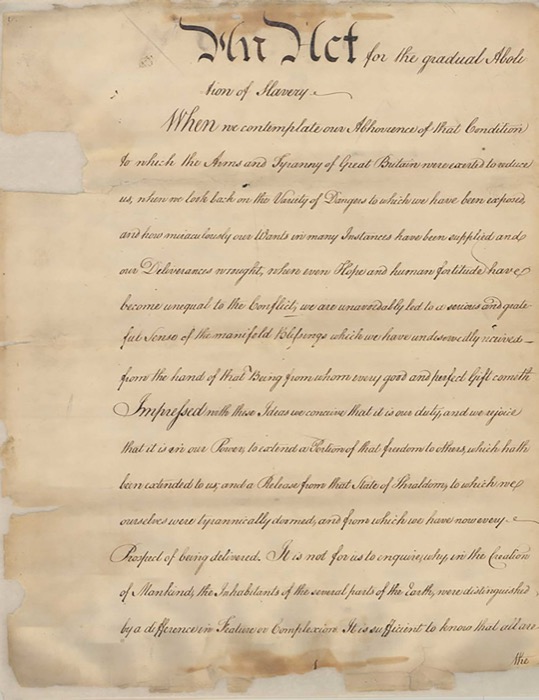

However, in 1768, under the nose of the next King George (III), legislators established a £10 duty on imported Negroes, then, in 1768, increased the duty to £20, made it perpetual, and strengthened enforcement and collection law. (see Negro Import Duties in Colonial Pennsylvania). Because of the long history of taxation in Pennsylvania, slave importation was tracked, and there was no recorded slave importation into Pennsylvania after 1767. The tax and Quaker expulsions achieved their objective; an impact noted by other colonies. Pennsylvania adopted an Act for Gradual Emancipation in 1780.

VIRGINIA: Virginia’s House of Burgesses first imposed a duty of £5 on imported slaves in 1704, which was vacated by the King. Richard Henry Lee proposed the 1769 Virginia bill intended to, in Lee’s words: “lay so heavy a duty on the importation of slaves as to put an end to that iniquitous and disgraceful traffic within the colony of Virginia.” (Richard Henry Lee – Bill of Rights Institute). Lee knew any attempt for outright abolition would be vetoed by the King, so he put a bill before the Virginia Legislature calling for a tax on the sale of slaves steep enough to curtail the practice.

The House of Burgesses adopted Lee’s additional tax of £20 on all slave sales in 1769, and reiterated it on 1 June 1770, which was signed by Virginia’s royal Governor; both were again vetoed in London by the King on the advice of the Board of Trade. They tried again in 1772 and wrote directly to the King petitioning his support on moral grounds. When it reached London, the Board of Trade argued strenuously against allowing Virginia colonists to set a self-asserted legal precedent that would be imitated in other colonies where importation was critical to EIC revenues, so again it was vetoed; this time with the Crown issuing a strict edict to governors prohibiting them from approving any such colonial legislation or sending it to the King for approval.

In 1769-1771 the Virginia Association adopted a boycott of British imports, including slaves, that impacted and promoted repeal of the Townshend Acts. Having had success with that form of economic “persuasion;” in the summer of 1774 multiple Virginia counties responded to the “Intolerable Acts” by adopting resolves that called for a fresh boycott of British goods, including slave importation. Virginia’s Convention of 1774 adopted those resolves, sending them with their delegates to Continental Congress as recommendations for broader implementation. Congress adopted such resolves on 20 Oct 1774. After that date, no slaves were ever legally imported into Virginia (in 1778 Virginia’s legislature formally banned importation of African slaves (“An Act For Preventing the Further Importation of Slaves,” Henning’s Statute at Large, vol 9, p 471-472); and in 1785 strengthened that act to automatically emancipate any enslaved person brought to Virginia from outside the state who remained for more than one year (Henning, vol 12, pp182-183).

NEW YORK: In 1773 the New York Assembly followed Virginia’s lead and attempted to impose a £20 duty on imported slaves, but the Royal Governor vetoed it per the King’s instruction; in retaliation New York’s rum distillation guild refused to provide rum to slave traders.

NEW JERSEY: Its legislature in 1762 imposed a £20 import duty on slaves to make it concurrent with its neighbors (New York and Pennsylvania). However, the Board of Trade in London instructed the Governor to veto the legislation. In 1773 the New Jersey assembly’s lower house (elected representatives) attempted to renew the act and doubled the duty, but again it was crushed by the Loyalist-leaning upper house; a council appointed by the Governor who acted on the instructions from the Board of Trade.

DELEWARE: On March 25, 1775 the legislature of the “Lower Three Counties of Pennsylvania on the Delaware” passed a bill outlawing importation of an enslaved person into the Colony, but Pennsylvania Governor John Penn refused to sign it on instruction from the King. This is interesting, because these counties were part of Pennsylvania at the time and the Penn family had permitted Pennsylvania’s assembly to effectively tax slave importation out of that colony – which included the Lower Three Counties on the Delaware (the “Lower Three Counties’” law subsequently went into effect on 20 June 1776 when Delaware declared its independence from Pennsylvania and elected its own assembly).

MARYLAND: In 1771 Maryland’s legislature imposed a £9 duty on slaves imported into the colony from anywhere. It’s believed that the legislature set the duty deliberately low enough to avoid veto from Baron Robert Eden, the relatively well-regarded, but newly appointed (and young – 28 years old) Royal Governor. There may have been some collusion between legislature and governor; Eden allowed it to stand.

CONNECTICUT: In 1650 Connecticut became the second colony to legalize slavery and passed draconian slave codes in 1660. Like Rhode Island, Connecticut ship owners profited richly from the transportation of slaves on charters from the East India Company and privately funded voyages. However, the enslaved could be emancipated legally in Connecticut if their owners pledged to support them should they become destitute.

The proportion of enslaved people began rising in the late 1760s, particularly in New Haven, reaching a peak of about 3% of the colony’s population by 1774. In November 1774 the Assembly of Connecticut, at the urging of Governor John Trumbull, passed an “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Indian, Negro, or Molatto Slaves,” outlawing all importation of slaves into the colony and installed a £100 fine for anyone caught doing so. The assembly cited both moral rationale as stated by Rev. Levi Hart as well as economic justification. (Levi Hart Calls for End to Slavery).

Governor Trumbull simply failed to inform the King or the Board of Trade, who had larger problems in Massachusetts at the time, that Connecticut had adopted such a law; and when the Board of Trade finally objected in May 1775, their complaint was moot: Connecticut militia was already a significant contingent of the American “Army of Observation” besieging Crown forces in Boston. In 1784 Connecticut passed a bill for gradual emancipation. Only 200 enslaved remained in the State by 1820, though Connecticut was the last New England state to officially abolish slavery in 1848.

MASSACHUSETTS: Massachusetts was the first American colony to officially sanction slavery in 1641, and first to legalize it in 1650. In 1764, when about 2% of Massachusetts’ population was enslaved, James Otis, an influential advocate for colonial independence, wrote that “The colonists are by the law of nature freeborn, as indeed all men are, white or black.” The Massachusetts Assembly’s Lower House (locally elected) attempted to curtail slavery via taxation in 1767 by passing a £40 duty on importation of slaves into the colony, but the Upper House (appointed by the Governor) unanimously non-concurred per the Governor’s instruction from King George III. (Duty on the importation of enslaved people)

Massachusetts’ constitution, the oldest in the world still in continual use, went into effect 25 Oct 1780. It states that “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties…” The Massachusetts constitution became the first to establish a “natural right” to freedom. In 1781 this constitutional guarantee was first used by Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman to successfully sue for her freedom.

The Drive to Save the East India Company

These attempts to curtail slavery in the American colonies were vetoed by the King upon urging and advice from the East India Company, the Board of Trade, and ultimately the King’s Privy Council, as being detrimental to Britain’s economic well-being and particularly to the profitability of the financially teetering British East India Company. By 1772 the “EIC” was the largest slave-trading company, and Britain the largest slave-trading nation, in the world. Virtually all enslaved Africans transported to what would become the USA were carried aboard British ships, the vast majority sailing for, or under contract to, the British East India Company. Further, of the 558 members of Parliament, most either held stock in “The Company” or were receiving inducements towards favorable disposition of EIC-related legislation.

The Company was in such dire financial distress that its impending failure threatened to ruin the British economy and the personal fortunes of many Parliamentarians. The British government did all it could to prevent a financial catastrophe caused by the ill-managed EIC, cancelling any colonial activity that could impact its profit margin. Vetoing American attempts to curtail slave trade and imposing trade laws favorable to the EIC – like the Tea Act (which granted the EIC a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies) – were not enough to stabilize the EIC. The situation became so dire that Parliament executed the first government mega-bailout of a corporate entity in 1773; a financial commitment so large that it may still be the largest corporate bailout in history. EIC survival became Parliament’s responsibility; and the EIC’s failed chief executive, Robert Clive, committed suicide with a letter opener.

South Carolina Objects

In October of 1774 the first Continental Congress agreed to a “Continental Association” which included an embargo of British imports, including slaves. Once the American Revolution broke out, the future of slavery in America passed into our own hands, and we’ve lost sight of how close our Founding Fathers came to abolishing slavery at Continental Congress in 1776.

When the Committee of Five drafted the Declaration, they knew that in the years leading up to the war eight colonies had voted to limit or outlaw slave importation; and that the embargo against slave importation had held for 21 months. It appeared then, as it does now, that there were sufficient votes in Continental Congress, eight to five, to support including a condemnation of chattel slavery in the Declaration of Independence; and to soon after take the next step of abolishing slavery in the new American nation. But… South Carolina objected; and threatened to withdraw from the alliance of united colonies, and to take Georgia and North Carolina with them, if the paragraph condemning slavery was not withdrawn.

It was a threat which could not be ignored. If the three southern colonies withdrew from the united alliance and remained loyal to Britain, British troops would be uncontested on Virginia’s doorstep, would cut off the covert flow of military goods up the Mississippi river, and the remaining ten colonies would have no hope of drawing in a foreign ally, no hope of defeating Britain, and would remain downtrodden British colonies subject to Parliamentary reprisals for the failed rebellion.

The anti-slavery paragraph was removed from the Declaration, and abolition was dropped from the conversation. However, the complaint that King George’s veto of the colonial attempts to tax slavery out of business still lives in the Declaration. The first of what we refer to as “justification statements” calling out the tyranny of King George III reads:

“He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

South Carolina Objects, Again

The process repeated itself at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. When the delegates assembled to write a new constitution their first order of business was to elect someone to preside over the convention, a “president.” They elected a man upon whom they knew they could trust: a man who could have been king of America and turned it down to be a farmer; George Washington.

Once again, delegates had good reason to believe that they had enough votes to ban slavery in a new draft of the Articles of Confederation or a fresh constitution, but they were beaten to the punch. In almost his first act as President of the Convention Washington recognized Charles Cotesworth Pinkney, from South Carolina, who rose to address the convention stating, paraphrased, that they were not there to debate the institution of slavery, and that if anyone did attempt to discuss abolition, the delegations from South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina would leave and align themselves with another foreign power. Once again, abolition was trumped by the need to hold the country together.

But, of course, slavery had to be discussed as a matter of interstate commerce, for taxation purposes, and for representation in Congress. Delegates agreed they would not attempt to abolish slavery for twenty years, giving time for South Carolina and Georgia planters to transition to wage-based labor. Three-fifths of the slave population would be counted towards a state’s delegates to the House of Representatives, giving slave-states an advantage in the House of Representatives that they would use to stiff-arm abolition of slavery; an incredible irony in that the very people giving them the votes to protect the institution of slavery were enslaved.

Historical Developments During the 20-Year Deferral of the Slavery Issue

Before that time expired in 1807 the face, tone, and brutality of slavery magnified due to a “perfect storm” intersection of factors that all occurred at or shortly after the turn of the century.

With the boycott of British goods adopted by the First Continental Congress on 20 October 1774, importation of slaves into America was embargoed until 1787 when Georgia made slave importation legal again, then South Carolina allowed its law prohibiting slave import to lapse in 1793. This caused Congress to begin legislating the very loop-holey Slave Trade Act of 1794 signed by President Washington, and the much tighter “Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves” (1807) which ended legal slave importation into the USA.

At the same time the invention of the cotton gin (1794) made cotton a viable replacement crop for the failing tobacco economy — increasing southern demand for field labor; and more land became available with the Louisiana Purchase (1803), acquisition of Florida (starting 1810), and the withdrawal (eviction) of native peoples in the southeastern states of Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi led to vastly expanded settlement opportunities that further intensified labor demand.

The failure to maintain the position of morality against South Carolina in 1776 and again in 1787 resulted in a compromise that doomed America to a civil war over slavery with 1.5 million casualties.

Conclusion – Maintaining Moral Principle

Moral lessons are often the most painful to learn. We’ve forgotten those who tried, even as colonials, to curtail slavery in America. We’ve forgotten them because their failure led to a national nightmare. In 1776, and again in 1787, there was a majority which could have ended slavery, but perceived the immediate threat to be greater than the long-term consequences of suppressing morality. America paid, and continues to pay, a horrible toll for that mistake. We must learn our history so that we don’t repeat it.

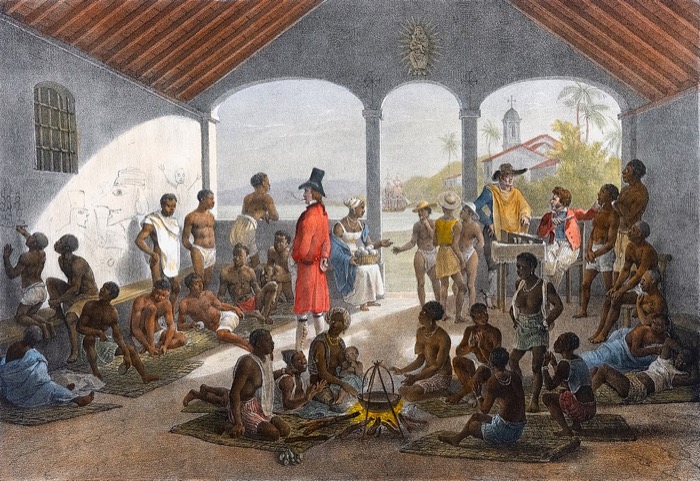

TOP PHOTO: A Slave Market in Brazil, Wilfredo Rafael Rodriguez Hernandez. The colonial era chattel slave-trade issue was much larger than the American colonies. Enslaved Africans brought to what is now the USA amounted to only about 3% of the total number carried by British ships and only 1% of the volume of African slaves transported by Britain, Portugal, Spain, France, Holland and others to their “new world” colonies, plantations, and mines. (Wilfredo Rafael Rodriguez Hernandez, CC0, via Wikimedia Common)